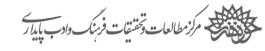

Chamran, Mustafa

Fatemeh Kasiri

1190 بازدید

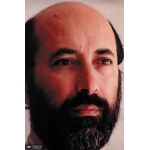

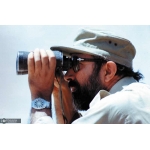

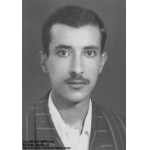

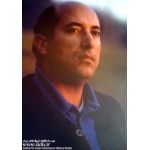

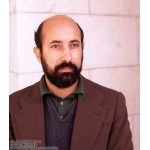

Mustafa Chamran (1932–1981) was one of the most influential figures in Iran and Lebanon. He served as Iran’s Defense Minister and founded the Irregular Warfare Headquarters during the Iran-Iraq War.

Mustafa Chamran was born in Tehran on March 9, 1933. He studied at Alborz and Dar ul-Funoun high schools. At the age of fifteen, he received religious education, including the interpretation of the Holy Quran, from Ayatollah Mahmoud Taleqani at Hedayat Mosque in Tehran. He also studied philosophy and logic under Ayatollah Morteza Motahari.[1]

In 1953, amid the political events surrounding the nationalization of Iran’s oil industry, Chamran began his political activities. After the 1953 coup and the fall of Muhammad Mossadeq’s government, Chamran joined the National Resistance Movement of Iran and was accepted into the Faculty of Engineering at the University of Tehran. On December 7, 1953, he was injured during protests at Tehran University against the visit of Richard Nixon, then Vice President of the United States.[2]

Chamran quickly became recognized as a talented and influential member of the Islamic Association of Students at the University of Tehran.[3] In 1958, he graduated from the University of Tehran with a bachelor’s degree in electromechanics and soon began teaching at the same faculty.[4] That year, he also received a scholarship to study at the University of Texas. After obtaining a master’s degree, he went on to earn his PhD in electrical engineering and plasma physics from the University of California, Berkeley.[5]

In 1961, Chamran became the first honorary and permanent member of the Iranian Students Association in the United States.[6] However, due to the organization’s political orientation, and with the help of a group of revolutionary youths, he founded the Muslim Students’ Association of America (MSA) in California. Due to his political activities against the Pahlavi regime, his scholarship was revoked.[7]

In 1961, Chamran married Tamsen H. Parvaneh. After being hired as a research staff scientist at Bell Laboratories—one of the most important scientific and industrial centers in the United States—he moved to New Jersey with his family. In 1963, he, along with Yazdi, left the U.S. for Egypt, where he was trained in guerrilla warfare. He subsequently assumed responsibility for training Iranian guerrilla fighters.

In 1967, Chamran returned to the United States, but in 1970, at the invitation of Imam Musa Sadr, the leader of Lebanon’s Shia community, he moved to Lebanon. After one year, due to the challenging living conditions in Lebanon, his wife returned to the U.S. with their children, and they later divorced.[8] In Lebanon, Chamran managed the Jabal Amel Technical School, and in 1977, he married a Lebanese woman, Ghadeh Jaber.[9]

In 1972–1973, Chamran joined the armed resistance against the Zionist regime in southern Lebanon and collaborated with Palestinian leaders, including Yasser Arafat. Following the kidnapping of his close friend and comrade, Imam Musa Sadr, on August 31, 1978, Chamran returned to Iran in 1979, after the victory of the Islamic Revolution, eager to meet Imam Khomeini (RA).[10]

In 1979, the Ministry of Defense of the Islamic Republic of Iran appointed Chamran to lead military operations against separatist activities in the city of Paveh, Kurdistan. Following Imam Khomeini’s historic order on the morning of August 18, 1979, and through Chamran and his comrades' resistance and efforts, Paveh was liberated on August 19, 1979.

On November 7, 1979, Imam Khomeini (ra) appointed Chamran as Minister of Defense, and on May 10, 1980, he became a member of the Supreme Council of National Defense, responsible for regularly reporting on the Army’s activities.[11] He was also elected to the Iranian Parliament as a representative of Tehran in 1980.[12]

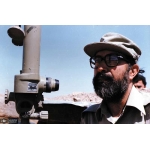

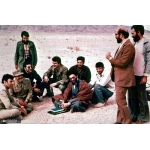

With the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War on September 22, 1980, Chamran, along with Ayatollah Seyyed Ali Khamenei (Imam Khomeini’s representative in the Supreme Council of National Defense and a member of the Iranian Parliament), traveled to Ahvaz and successfully led the first guerrilla attack against the advancing Baathist forces near Ahvaz. Chamran then established the Irregular Warfare Headquarters in coordination with the Army, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), and local volunteer forces in Ahvaz.[13]

Chamran’s efforts to create an active engineering unit within the Irregular Warfare Headquarters led to the construction of military roads in various locations. By installing water pumps near the Karun River and constructing a canal within a month, he directed water towards Iraqi tanks, preventing them from making headway.[14]

In 1980, Chamran was injured during an operation conducted by the Army, the IRGC, and irregular forces to liberate Susangerd. However, before fully recovering, he returned to the frontlines. On May 21, 1981, through a joint operation involving forces from the Army, the IRGC, and the Irregular Warfare Headquarters, the Iranians successfully captured the Allahu Akbar Heights and Dehlavieh.[15]

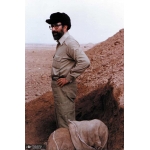

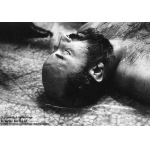

On June 21, 1981, Mustafa Chamran was wounded while inspecting trenches in southern Iran (Dehlavieh) when a mortar shell fragment struck the back of his head. Although he received initial treatment at Susangerd Hospital, he was martyred while being transported to Ahvaz Hospital in an ambulance. A funeral ceremony was first held for him in Ahvaz, and later in Tehran in front of the Iranian Parliament. On June 23, 1981, Chamran was buried in Section 24 of Behesht-e Zahra Cemetery in Tehran. A memorial was erected at the site of his martyrdom near the Susangerd–Bostan Road.[16]

Many of Chamran’s prayers and mystical writings have been recorded. Some of his works, compiled by his brother Mahdi Chamran and published by the Martyr Chamran Foundation, include Daily Memories titled There was God and Nothing Else, Jihad and Martyrdom, and Ali: The Most Beautiful Poem of Life. His speeches have also been collected in volumes such as Man and God, Kurdistan, and Lebanon. Moreover, his mystical reflections and concise reports on the heroic battles of the Iran-Iraq War are also documented.[17]

The short film In Memory of the Martyred Commander Dr. Chamran, directed by Muhammad Reza Pasdar, was released in 1982.[18] Also, in 2014, a movie named Che, directed by Ebrahim Hatamikia, was released to honor Chamran. The film portrays two days of his life during the battles in Paveh.[19] Between 1993 and 1996, the television series Simorgh was produced, highlighting the role of Chamran, as well as two pilots, Ahmad Keshvari and Ali Akbar Shiroodi, in the Paveh incident.[20]

[1] Encyclopedia of the Islamic Revolution for Teenagers and Young People, Vol. 2, Tehran: Soure Mehr, 2005, p. 60.

[2] Ibid., pp. 60 and 61; Yaran Emam Be Revayat Asnad Savak (Imam's Companions According to SAVAK Documents), Vol. 11: Martyr Sarafraz Dr. Mustafa Chamran, Tehran: Center for the Study of Historical Documents of the Ministry of Intelligence, 1999, p. 5.

[3] Najafpour, Majid, Parastoye Dehlavieh, Tehran: Cultural and Artistic Institute and Islamic Revolution Documents Center, 2014, pp. 30 and 37.

[4] Yaran Imam, according to SAVAK documents, vol. 11, p. 6.

[5] Najafpour, Majid, Parastoye Dehlavieh, p. 38.

[6] Yaran Imam, according to SAVAK documents, vol. 11, p. 7.

[7] Najafpour, Majid, Parastoye Dehlavieh, pp. 40-42.

[8] Ibid., pp. 46, 62, and 76; Yaran Imam, according to SAVAK documents, vol. 11, p. 9.

[9] Jafarian, Habibeh, Nimeh Penhan Mah 1: Chamran as Narrated by the Martyr's Wife, Tehran: Revayat Fath, 1999, p. 11; Najafpour, Majid, Parastoye Dehlavieh, p. 63.

[10] Najafpour, Majid, Parastoye Dehlavieh, pp. 99 and 100.

[11] Encyclopedia of the Islamic Revolution for Teenagers and Young People, Vol. 2, p. 62; Najafpour, Majid, Parastoye Dehlavieh, p. 135.

[12] Memorial of the first anniversary of the martyrdom of Martyr Dr. Mustafa Chamran, Martyr Chamran Foundation, 1982, p. 15; Encyclopedia of the Islamic Revolution for Teenagers and Young People, Vol. 2, p. 62.

[13] Memorial of the first anniversary of the martyrdom of Dr. Mustafa Chamran, pp. 15 and 16.

[14] Jafarpour, Majid, Parastoye Dehlavieh, pp. 153 and 154.

[15] Ibid., p. 175; Memorial of the first anniversary of the martyrdom of Dr. Mustafa Chamran, pp. 17-20; Yaran Imam according to the narration of SAVAK, vol. 11, p. 32.

[16] Fattahi, Shiva, Tekehee Az Asman Dehlavieh, Tehran: Sacred Defense Art and Literature Organization, 2014, p. 72; Encyclopedia of the Islamic Revolution for Teenagers and Young People, Vol. 2, p. 62.

[17] Shahed Yaran, Vol. 37, December 2008, p. 72.

[18] Farasti, Masoud, Culture of Iranian War and Defense Films (1970-2012), Tehran: Saqi, 2013, p. 310.

[19] Cinema Monthly Film, Year 32, No; 473, May 2014, p. 60.

[20] Ibid., No. 245, November 26, 1999, pp. 110 and 111.