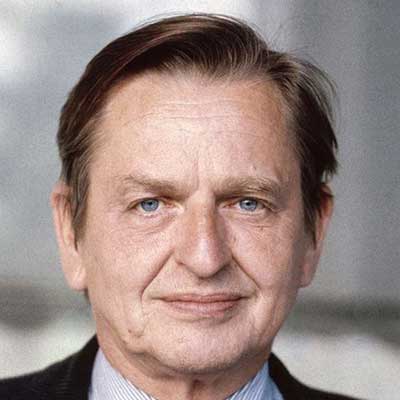

Palme, Olof

Leila Heydari Bateni

328 بازدید

Sven Olof Joachim Palme (1927–1986) was the former Prime Minister of Sweden and the leader of the Swedish Social Democratic Workers' Party. During the Iran-Iraq War, he visited both countries several times as a representative of the UN Secretary-General. Despite his efforts and negotiations with both governments, his mission to broker peace ultimately failed.

After the Iran-Iraq War broke out on September 22, 1980, Kurt Waldheim, the fourth UN Secretary-General, initiated efforts to mediate and bring the two countries to the negotiating table. On October 10, 1980, Waldheim called for a truce to free merchant ships trapped in the conflict and to facilitate legal international trade. In response, Iran agreed, via two letters to the UN, to ensure the safety of commercial ships passing through the Arvand River and the ports of Khorramshahr, Abadan, and Basra under the UN flag. However, Iraq rejected the proposal, citing its claim of sovereignty over the Arvand River.[1]

As peace talks faltered, Waldheim proposed appointing a high-ranking political figure to mediate—a suggestion accepted by the Security Council.[2] On November 11, 1980, Waldheim informed the Security Council that both Iran and Iraq had agreed to his appointment of Olof Palme as the UN’s special representative to the region.[3] Palme, who had served as Prime Minister of Sweden (1969–1976) and led the Swedish Social Democratic Workers' Party, began his work as the special mediator for the UN.[4]

Palme had a history of political activism, including opposition to apartheid in South Africa, protests against the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia, and anti-war demonstrations in Stockholm.[5] His main task as mediator was to address the issue of commercial ships passing through the Persian Gulf, which were being threatened by air and naval attacks from both Iraq and Iran. To begin, Palme and Diego Cordovez, the Under-Secretary-General, first traveled to the UN Security Council headquarters in New York to review the UN’s ceasefire proposal before heading to Iran.[6]

Five rounds of negotiations were held in Iran and Iraq as Palme sought a plan that would allow ships to pass safely through the Persian Gulf despite the ongoing conflict. He was aware of the significant costs associated with such a plan and proposed that both Iran and Iraq share the necessary resources. However, both countries rejected his ceasefire proposals.[7] Iraq’s insistence on its sovereignty over the Arvand River and its demand that Iran cover the entire cost of the operations contributed to the failure of Palme’s efforts. During his second visit to the region, on January 15–16, 1981, Saddam Hussein announced that Iraq would withdraw from Iran only if its rights over the Arvand River were recognized.

In February 1981, after his third visit to Iran and Iraq, Palme concluded that the two governments needed to jointly manage the river.[8] Despite holding five rounds of negotiations between November 1980 and February 1981 in both Tehran and Baghdad, Palme was unable to persuade the countries to agree to a ceasefire.[9] On June 21, 1981, Palme met with Hojatoleslam Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, the Speaker of the Iranian Parliament. During the meeting, Palme called for an end to the war without requiring Iraq to make significant concessions. However, he rejected Iran’s demand for the unconditional withdrawal of Iraqi forces from Iranian territory, urging Iranian officials to continue negotiations. Iran also declined Palme’s ceasefire proposal during Ramadan, which he had conveyed to Iran’s ambassador in Geneva on July 3, 1981.[10]

In February 1982, Palme again visited Baghdad and Tehran to provide further details on his plan. However, his efforts once again yielded no results, and he ultimately concluded that any mediation would be futile unless both parties genuinely sought peace.[11]

On February 27, 1982, during another visit to Iran, Palme discussed the peace process with the then-President of Iran, Ayatollah Seyyed Ali Khamenei. Iran set three conditions for peace: the unconditional withdrawal of Iraqi forces from Iranian territory, reparations, and punishment of the aggressor. Palme agreed to the first condition and called for the continuation of negotiations with international observers to resolve border disputes. He also suggested that volunteer states could contribute reparations to both sides, urging Iran to show leniency and accept a ceasefire.[12]

On March 9, 1982, Hojatoleslam Hashemi Rafsanjani described his five-hour negotiations with Palme as fruitless, stating in an interview, "We and the mediation team concluded that Iraq would not surrender without pressure." Palme's mediation team emphasized that their role was not to pass judgment but to mediate and establish peace between the warring parties. They suggested that if Iran made concessions, Iraq would reciprocate. Ultimately, it was agreed that Palme would present the results of these discussions at the next Islamic Conference.[13]

On October 7, 1982, in a report to the United Nations, the Secretary-General stated that despite multiple visits to Iran and Iraq and discussions with officials from both countries, Palme had made no progress toward achieving peace or a ceasefire.[14]

After Kurt Waldheim's tenure as UN Secretary-General ended, Palme continued as a representative under the new Secretary-General, Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, but made no significant breakthroughs in the negotiations. On January 4, 1983, Sweden's ambassador to Iran requested that Palme, who had recently been reappointed Prime Minister of Sweden,[15] visit Iran to continue his mediation efforts.[16]

Palme served again as Sweden’s Prime Minister from 1982 to 1986. His foreign policy positions—including his role in mediating the Iran-Iraq War, his support for the Palestinian Liberation Organization, his opposition to apartheid, and his harsh criticism of the US government’s involvement in the Vietnam War—earned him both challenges and enemies. Olof Ruin, a historian and professor of political science at Stockholm University, noted that Palme's background and political activities were significant, stating, "Palme was the first to draw the Swedish public's attention to the issue of Palestine. Since World War II, Swedish policymakers had been staunch supporters of Israel, but Palme made us aware of the exiled Palestinians."[17]

On February 28, 1986, Olof Palme was assassinated by an unknown assailant.[18] His killer was never identified. Two weeks later, a funeral was held in Stockholm under tight security, attended by leaders from 119 countries.[19] Swedish authorities then tasked a fact-finding committee with investigating Palme's assassination. Based on the committee's secret report, various organizations and individuals—including the apartheid regime of South Africa, the Kurdish militant group PKK, the CIA, and the Swedish secret police—were charged but later acquitted. Among those arrested in connection with Palme’s murder was Amir Heydari, an Iranian fugitive accused of human trafficking.[20] He was allegedly seeking to sabotage relations between Iran and Sweden. However, due to a lack of conclusive evidence, Heydari was acquitted and released.[21]

[1] Kurt Waldheim, The Glass Palace of Politics

[2] Kurt Waldheim, The Glass Palace of Politics

[3] Mosfa, Nasrin, Tarem Sari, Masoud, Alam, Abdolrahman, Mostaqimi, Bahram, Iraq's aggression against Iran and the United Nations' stance, p. 169; Khorami, Mohammad Ali, The Iran-Iraq War in United Nations Documents, vol. 1, p. 73.

[4] Lotfollahzadegan, Alireza, Iran-Iraq War Calendar, Book Eleven: Hoveyzeh, the Last Steps of the Invaders, Tehran: Center for War Studies and Research, 1994, pp. 133, 249, 267, and 279.

[5] Sharq Newspaper, No. 715, March 7, 2006, p. 19.

[6] Kurt Waldheim, The Glass Palace of Politics

[7] Lotfollahzadegan, Alireza, Iran-Iraq War Calendar, Book Eleven: Hoveyzeh, the Last Steps of the Invaders, Tehran: Center for War Studies and Research, 1994, pp . 133, 279, 267, 249.

[8] Mosfa, Nasrin, Tarem Sari, Masoud, Alam, Abdolrahman, Mostaqimi, Bahram, Iraq's aggression against Iran and the United Nations' stance, p. 169; Khorami, Mohammad Ali, The Iran-Iraq War in United Nations Documents, vol. 1, pp; 169 and 170.

[9] Lotfollahzadegan, Alireza, Iran-Iraq War Calendar, Book Eleven: Hoveyzeh, the Last Steps of the Invaders, Tehran: Center for War Studies and Research, 1994, pp . 133, 279, 267, 249.

[10] Hashemi, Yaser, Gozar Az Bohran (Passing the Crisis): The Report Card and Memoirs of Hashemi Rafsanjani, Tehran: Maarif Enghelab Publishing House, 1999, pp. 166-187.

[11] Kurt Waldheim, The Glass Palace of Politics

[12] Hashemi, Yaser, Gozar Az Bohran (Passing the Crisis): The Report Card and Memoirs of Hashemi Rafsanjani, Tehran: Maarif Enghelab Publishing House, 1999, p. 495.

[13] Hashemi, Mohsen, Hashemi Rafsanjani Interviews of 1981, Vol. 1, Tehran: Maarif Enghelab Publishing House, 1999, pp. 318-320.

[14] Khorami, Mohummad Ali, The Iran-Iraq War in UN Documents, Vol. 1, p. 31.

[15] Mosfa, Nasrin, Tarem Sari, Masoud, Alam, Abdolrahman, Mostaqimi, Bahram, Iraq's aggression against Iran and the United Nations' stance, p. 169; Khorami, Mohammad Ali, The Iran-Iraq War in United Nations Documents, vol. 1, pp; 169 and 171.

[16] Hashemi, Fatemeh, After the Crisis: Hashemi Rafsanjani's Report Card and Memoirs in 1982, Tehran: Maarif Enghelab Publishing House, 2001, pp. 353 and 354.

[17] Sharq Newspaper, No. 715, March 7, 2006, p. 19; Sharq Newspaper, No. 716, March 8, 2006, p. 19.

[18] Ibid

[19] Islamic Republic Newspaper, No1986, March 16, 1985, Year 7, p. 3.

[20] Sharq Newspaper, No. 715, March 7, 2006, p. 19; Sharq Newspaper, No. 716, March 8, 2006, p. 19.

[21] https://aftabnews.ir/fa/news/416404