Terms & Concepts

Flooding

Written by: Mohsen Shirmuhammad,

Translated by: Hadi Qorbanyar

28 دورہ

One of the defensive tactics employed by Iranians during the Sacred Defense was the deliberate release of water into areas between friendly and enemy forces to impede Iraqi advances.

Since ancient times, using water as a weapon in warfare has been a common practice. Examples include the digging of a canal in 596 BC by Nebuchadnezzar (King of Babylon) to capture the city of Tyrus (Lebanon); the diversion of the Arno River towards the city of Pisa (Italy) during the war between Florence and Pisa in 1503; and the breaching of the Bar Lev Line (the Israeli regime) along the Suez Canal by the Egyptian army in the 1973 war using high-pressure water.[1]

During the imposed war of Iraq against Iran, water was likewise employed as a military tactic by both sides. With the enemy’s advances in the first month of the war (October 1980), and despite the initial resistance of the Iranian armed forces and the people, some of the western cities of Khuzestan were about to collapse.[2] Therefore, military and political officials decided to release the waters of the Karun, Karkheh, and Karkheh-Kor (a branch of the Karkheh) rivers into the southern plains of Ahvaz, in order to create artificial barriers against the enemy’s advance, particularly the movement of its armored units towards Ahvaz.[3] Some even suggested blowing up the Dez Dam so that the floodwaters would wash away the Iraqi army. After much debate, however, they decided not to destroy the dam and instead, release larger amounts of water to flood the southern areas of the Ahvaz–Susangerd Road.[4] Brigadier General Valiollah Fallahi (martyred) and Dr. Mustafa Chamran (martyred) were the main planners of this artificial flood.[5]

The man-made flood was created in three areas: southwest of Ahvaz between the Karkheh-Kor and Karun rivers, using their waters; south of the Hamidiyeh–Susangerd axis, using water from the Karkheh; and west of the Karun River, from south of Ahvaz to Khorramshahr.[6]

The flooding project began in early 1981, under the supervision of the Khuzestan Governor’s Office and the Khuzestan Water and Power Authority, which undertook the excavation of canals, the construction of dams on the Karkheh, and the pumping of water from the Karun.[7]

To implement the plan in Karkheh-Kor, an earthen dam was constructed in February 1981 on the northern branch, located in the area north of the village of Azdak, by the Khuzestan Water and Power Authority.[8] Since the Karkheh-Kor drew its water from the Karkheh River[9] via a diversion from the Karkheh Dam, the flow was controlled through the dam’s gates. Accordingly, the gates were lowered to allow more water to build up behind the dam. Once sufficient water had been stored, the gates were closed and the entire flow of the Karkheh was directed into the diversion canal, then poured into the Karkheh-Kor. Because the Karkheh-Kor, due to its limited width and depth, could not contain the Karkheh’s full discharge, and also an earthen dam had been built north of Azdak, the river overflowed in the southeast of Hamidiyeh, submerging low-lying lands and creating an impassable swamp.[10]

Consequently, on February 14, 1981, the 16th Armored Division of the Iranian Army was able to withdraw part of its units from the area, thus enabling them to engage in other operational zones.[11]

In February 1981, the Khuzestan Water and Power Authority excavated a wide canal on the bank of the Karun River, north of the Ahvaz–Andimeshk police station. The canal extended along the northern and western approaches to Ahvaz.[12] As part of the operation, Karun’s water was pumped into the dug canal by nine pumps. The water flowed into the plain near Dub—Hardan in southwest Ahvaz, turning part of the area into a swamp,[13] and thereby providing a natural barrier that secured Iranian defensive positions. These fortifications remained operational until Operation Beit al-Muqaddas, approximately 15 months later.[14]

Also, in mid-February 1981, the Khuzestan Water and Power Authority built an earthen dam on the Karkheh River between Hamidiyeh and Susangerd.[15] During the same period, a canal was dug from the river to the southern plain along the Hamidiyeh–Susangerd Road[16] by the same authority.[17] According to these plans, Karkheh’s water pooled behind the earthen dam and then flowed into the constructed canal. Ultimately, the canal’s water entered the plain south of the Hamidiyeh–Susangerd Road, flooding part of the area and preventing the enemy’s movement.[18]

Also, the gates of the Dez Dam were opened on January 19, 1981,[19] and with the rise in the Karun’s water level the lands southwest of Ahvaz were flooded, becoming marshland and immobilizing the enemy.[20] Flooding the region to impede the enemy’s advance was of great importance to Iran’s authorities at the time. The then–President Abulhassan Banisadr monitored these measures closely.[21] In a letter to Imam Khomeini (ra) dated March 8, 1981, he wrote that Iran’s hopes of confronting the enemy depended entirely on the successful implementation of the water plan.[22]

These measures led to flooding in parts of southern Ahvaz, which effectively prevented the Iraqi troops from advancing through the area. Furthermore, fortifications southwest of Ahvaz and along the southern Hamidiyeh–Susangerd axis were strengthened, substantially diminishing the immediate threat to southern Ahvaz. By carrying out the plan, the danger of Ahvaz falling from the west and Hamidiyeh was reduced, and Susangerd faced less threat from the east and south. However, opening the Dez Dam gates and creating artificial floods in the Karun had adverse effects as well, including[23] the destruction of the Hamidabad Bridge on the Shush–Dezful–Shushtar axis over the Dez River.[24]

Although this plan proved effective in strengthening Iran’s defensive positions, it could also be exploited by Iraqi forces. By late 1980, as the enemy was forced into a defensive posture and ceased its attacks, it became clear that Iranian troops were unable—and unwilling—to attack from the waterlogged area. Consequently, Iraq was able to transfer many of its troops from that area to reinforce other units.[25]

Later on, in October 1984, and after completion of the Salman water-transfer installations and canal (southwest of Ahvaz), a one-hundred-kilometer channel built by Jahad-e Sazandegi Organization, water was released into the Jufair, Koushk, and Talaieh plains. By creating physical obstacles and drawing the enemy into flood-control and construction efforts, Iranian forces were able to free up and redeploy part of their units to other areas.[26]

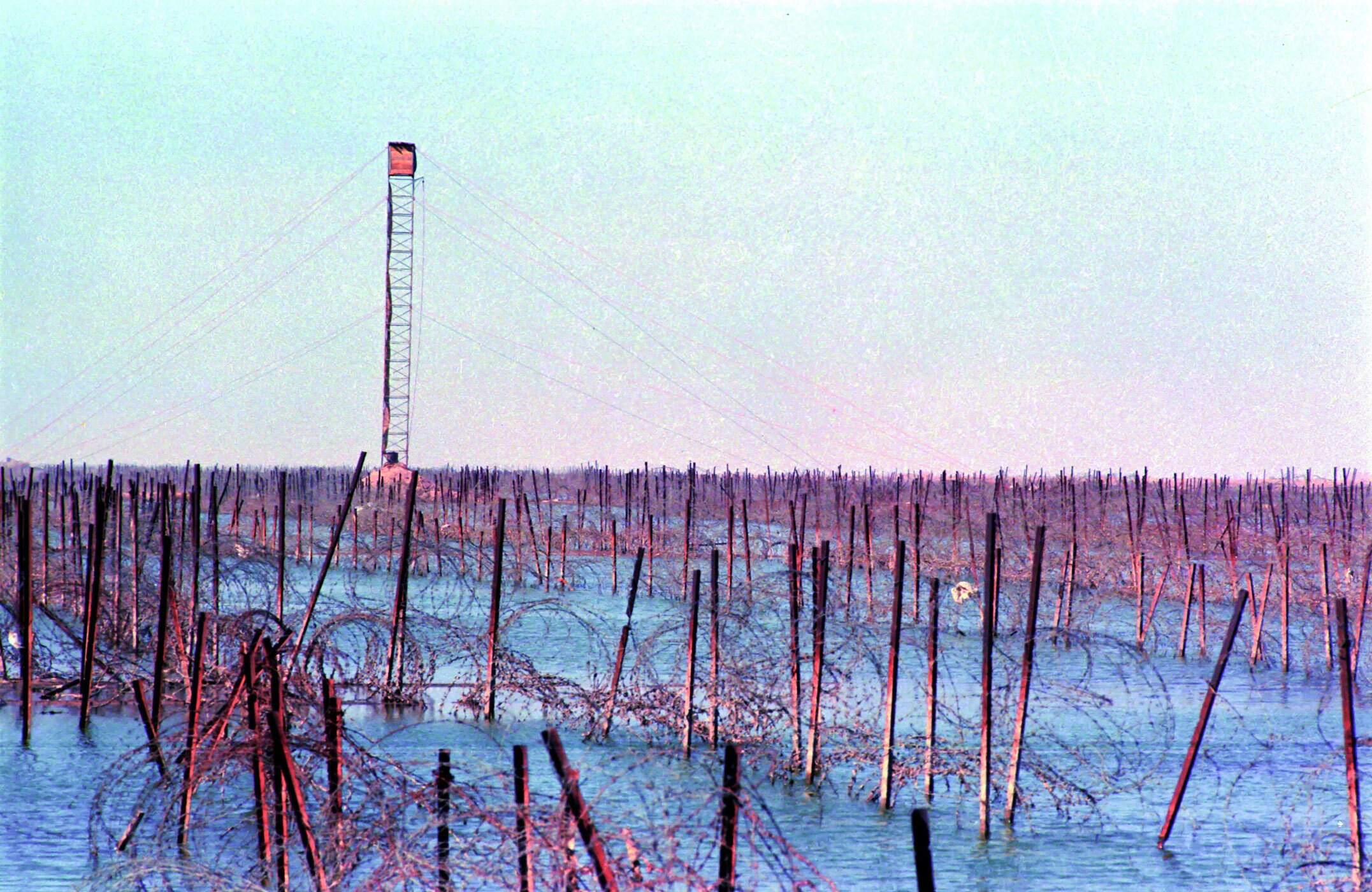

Iraq also employed the tactic of flooding for the first time during Operation Ramazan (July 1982). By releasing water and expanding flooded zones in this operation, the enemy slowed down Iran’s military maneuvers, engineering activities, and even the movement and relocation of infantry. Iraq fortified part of this area with triangular embankments. Moreover, it had constructed a 29-kilometer canal for fish farming along its border with Iran from Shalamcheh to the Zayd outpost.[27] The enemy then flooded the surrounding terrain, turning it into marshland and cutting off access, making any movement by Iranian forces extremely difficult if not impossible. The area was covered by 40 to 50 centimeters of water.[28]

During Operation Karbala 5 (January 1987), Iraq created a range of obstacles in the flooded zones, such as barbed wire and hedgehog anti-vehicle barriers. The enemy manipulated the water level so that neither boats nor divers could cross, i.e., the depth was maintained between 50 and 150 centimeters. Therefore, the shallow depth prevented the passage of large boats, while at the same time, divers were unable to swim. In the first phase of Operation Karbala 5, Iranian divers were supposed to break through the frontline, but in practice, they were forced to walk in some areas and swim in others. After breaching the enemy defensive lines, light flat-bottom boats and Khashayar armored personnel carriers were used to support the advancing troops. Despite the flooding measures by the Iraqis, Operation Karbala 5 was carried out successfully.[29]

Iran was employing the tactic of controlled flooding until the acceptance of UN Security Council Resolution 598 in 1987 and even afterwards as a defensive measure. For instance, at the time of the ceasefire, water released through the Salman Canal flooded a 2.5-kilometer area between Iranian and Iraqi fortifications, extending from Talaieh to the Khin River in the southwestern border zone of Khuzestan.[30]

[1] Shirmuhammad, Mohsen, Estefade az Ab be Onvane Yek Selah-e Nezami (Using Water as a Military Weapon), Mahnameh Saf, No. 317, Azar 1385, p. 19.

[2] Shirmuhammad, Mohsen, Cheshman-e Oqab: Hamaseh-ye Gordan 11 Shenasayi-e Taktiki-ye Niruye Havaei va Amaliat-e Aksbardari-e Havaei dar Defa Muqaddas (Eagle Eyes: The Epic of Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron 11 of the Air Force and Aerial Photography Operations in the Sacred Defense), Tehran, Markaz Entesharat Rahbordi-ye NAJA, 1396, Pp. 179.

[3] Ibid., p. 179.

[4] Ardestani, Hussain, Tarikh Shafahi-ye Defa Muqaddas, Revayat-e Seyyed Yahya Safavi, Vol. 1: Az Sanandaj ta Khorramshahr (Oral History of the Sacred Defense: The Narrative of Seyyed Yahya Safavi, Vol. 1: From Sanandaj to Khorramshahr), Tehran, Markaz Asnad va Tahqiqat-e Defa Muqaddas, 1397, p. 238.

[5] Shirmuhammad, Mohsen, Cheshman-e Oqab: Hamaseh-ye Gordan 11 Shenasayi-e Taktiki-ye Niruye Havaei va Amaliat-e Aksbardari-e Havaei dar Defa Muqaddas (Eagle Eyes: The Epic of Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron 11 of the Air Force and Aerial Photography Operations in the Sacred Defense), p. 179.

[6] Hussaini, Yaqoub, Seil-e Masnui baraye Padafand dar Khuzestan (Artificial Flooding for Defense in Khuzestan), Tehran, Iran Sabz, 1392, p. 33.

[7] Ibid., p. 33; Shirmuhammad, Mohsen, Cheshman-e Oqab: Hamaseh-ye Gordan 11 Shenasayi-e Taktiki-ye Niruye Havaei va Amaliat-e Aksbardari-e Havaei dar Defa Muqaddas (Eagle Eyes: The Epic of Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron 11 of the Air Force and Aerial Photography Operations in the Sacred Defense), p. 179.

[8] Ibid., Pp. 150, 33.

[9] Ibid., p. 33.

[10] Ibid., p. 34.

[11] Ibid., Pp. 152, 153.

[12] Ibid., Pp. 34, 35.

[13] Ibid., p. 34.

[14] Ibid., p. 149.

[15] Ibid., Pp. 150–152.

[16] Ibid., p. 34.

[17] Ibid., Pp. 150–152.

[18] Ibid., p. 35.

[19] Ibid., p. 146.

[20] Shirmuhammad, Mohsen, Cheshman-e Oqab: Hamaseh-ye Gordan 11 Shenasayi-e Taktiki-ye Niruye Havaei va Amaliat-e Aksbardari-e Havaei dar Defa Muqaddas (Eagle Eyes: The Epic of Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron 11 of the Air Force and Aerial Photography Operations in the Sacred Defense), p. 179.

[21] Sohrabi, Pejman, Mamuriyat-e Shabah 5 (Phantom 5 Mission), Tehran, Markaz Entesharat Rahbordi-ye NAJA, 1397, p. 172.

[22] Banisadr, Firoozeh, Nameha az Aqaye Banisadr be Aqaye Khomeini va Digaran (Letters from Mr. Banisadr to Ayatollah Khomeini (ra) and Others), 1384, p. 168.

[23] Hussaini, Yaqoub, Ibid., p. 35.

[24] Ibid., p. 36.

[25] Ibid., p. 36.

[26] Pourjabari, Pejman, Atlas-e Joghrafi-ye Hamasi 1: Khuzestan dar Jang (Epic Geography Atlas 1: Khuzestan in War), Tehran, Sarir, 1389, p. 206.

[27] Heydari Moqaddam, Abbas, Hendeseh dar Razm – Tarikh Shafahi-ye Mohandesi-ye Razmi-e Defa Muqaddas, Vol. 2 (Geometry in Combat – Oral History of Combat Engineering in the Sacred Defense, Vol. 2), Tehran, Entesharat-e Mozeh Enqelab Eslami va Defa Muqaddas, 1398, p. 165.

[28] Ibid., p. 166.

[29] Barrasi-ye Chegoonegi-e Anjam-e Amaliat-e Karbala 5 va Nahve-ye Shekast-e Khat-e Doshman dar in Mantaqeh (Studying Operation Karbala 5 and the Method of Breaking the Enemy Line in this Area), Markaz Asnad va Tahqiqat-e Defa Muqaddas, 9 Dey 1399, www.defamoghaddas.ir/news/625

[30] Khodaverdi, Mahdi, Barrasi-ye Taktik-e Ab dar Jang-e Tahmili-ye Araq bar Iran (Review of Water Tactics in the Iran-Iraq War), Faslnameh Negin-e Iran, No. 32, Bahar 1389, p. 102.