Battles

Muharram

Leila Heydari Bateni

218 Views

Operation Muharram was carried out under the joint command of the Islamic Republic of Iran Army and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) in the south of Dehloran and the western part of Ain Khosh, Ilam Province. The main objectives of the operation included liberating the heights across the border (Hamrin) and capturing the bridgehead area of al-Amarah. The operation concluded after the goals were partially achieved.

In early 1982, the Iranian War Central Command adopted the strategy of driving Iraqi forces out of Iranian territory by following the enemy into Iraq. After Operation Ramazan (July 1982), Iranian forces shifted their military offensives from eastern Basrah to the Sumar–Mandeli region. Iraq, while controlling significant heights across the border, had the Dehloran Road—the closest supply route to Iran’s central and southern fronts—within its artillery range thereby easily attacking the oil facilities and installations in Bayat. As a result, a series of limited offensive operations such as Moslim ibn Aqil in western Sumar and Muharram in southeastern Dehloran and western Ain Khosh were carried out during October–November 1982. The purpose of these operations was to fill the gap between launching large-scale operations, saving time, enhancing the forces’ military capabilities, fully achieving the objectives of previous operations, keeping the fronts active, neutralizing and seizing the initiative, mobilizing public support, and countering anti-Iran propaganda.[1]

On October 12, 1982, the Karbala Headquarters, responsible for devising the strategic and tactical components of such operations, sent the operational plan of Operation Muharram to Fath Headquarters.[2]

The objectives of the operation included the liberation of the strategic Hamrin Heights and several border outposts and oil fields, the capture of the bridgehead in al-Amarah, helping Iranian forces reach the international borders, taking the Ain Khosh–Dehloran Road out of enemy artillery range, deploying Iranian forces to the strategic positions on the mountains, reinforcing a broad defensive line across an open plain by deploying troops to Hamrin Heights and putting observation posts to watch the Basra–Amarah Road as well as enemy supply routes and towns. Moreover, jeopardizing Iraq’s Tayyib industrial complex, liberating the Zubeidat, Sharhani, and Abu Ghuraib outposts, seizing Iraq’s oil wells in these areas, and dispersing the Iraqi forces on the southern fronts were among other objectives of the operation.[3]

Operation Muharram was launched on the border and mountainous regions west of Ain Khosh in southeastern Musian and Dehloran. The area was bounded by Bayat oil fields to the north, Jabal Foqi to the south, the Doveiraj River to the east, Hamrin Heights and the Iraqi cities of al-Amarah and Ali al-Gharbi to the west. 900 kilometers of this 1,500-square-kilometer area were located in Iraqi territory. The eastern bank of the Tigris River, between the cities of al-Amarah and Ali al-Gharbi in Iraq, became, as the eastern Basrah, a strategic zone for Iraq since it had occupied the heights in the area, the city of Musian, and its oil wells two years ago thereby gaining control over Iran’s communication lines. Therefore, whenever Iraq felt threatened, it would immediately bombard the Dehloran–Ain Khosh Road.[4]

The combat organization of the operation was under the command of Qaem Headquarters, which included Qaem 1 to Qaem 6 sub-headquarters. Qaem 1 was composed of ten infantry battalions, one anti-armor battalion, two artillery battalions from the 8th Najaf Ashraf Brigade, one gendarmerie company from Musian, one 105-mm artillery battalion from the Army, and one 122-mm artillery unit from the IRGC, all of which were under the command of Ahmad Kazemi. Qaem 2 consisted of seven infantry battalions from the 25th Karbala Brigade of the IRGC. Qaem 3 included eight infantry battalions from the 17th Ali ibn Abi Talib (as) Brigade of the IRGC which commanded by Mahdi Zeinoddin, and the 1st Brigade of the 21st Hamzeh Division of the Army led by Colonel Ali Razmi. Qaem 4 included ten infantry battalions, one armored battalion, one air defense battalion, and one artillery battery from the 14th Imam Hussain (as) Brigade, four infantry battalions, one tank battalion, one artillery battalion, and one armored cavalry company from the 84th Khorramabad Brigade, all of which were under the joint command of Muhammad Abushahab (commander of the 14th Imam Hussain (as) Brigade of the IRGC) and Colonel Eskandar Beiranvand (commander of the 1st Brigade of the 21st Hamzeh Division of the Army). Led by Karim Nasr (commander of the 44th Qamar Bani Hashem (as) Brigade of the IRGC), Qaem 5 consisted of two infantry battalions from the 44th Qamar Bani Hashem (as) Brigade and one commando battalion from the 58th Brigade. Also, Qaem 6 comprised six infantry battalions from the 35th Imam Sajjad (as) Brigade, and commanded by Muhammad Nabi Roudaki (commander of the 35th Karbala Brigade). In total, these units comprised sixty infantry battalions (fifty-two from the IRGC and eight from the Army) and two battalions from the Gendarmerie whereas the enemy’s deployed combat force—specifically the 10th Armored Division of the 4th Corps of the Iraqi Army—was twice more powerful than Iranians in terms of military equipment and combat power.[5]

The importance of this operation led Saddam Hussain to personally supervise and direct the offensive, utilizing all available resources to prevent the Iranian advance.[6]

Operation Muharram (Operational Plan Karbala 5) began at 10:05 PM on November 1, 1982, with the code-name “Ya Zaynab (s)”, under the command of the Qaem Central Headquarters. The operation was led by Hussain Kharrazi, commander of the Fath Headquarters from the IRGC and Colonel Manouchehr Dejakam from the Army. Since the operation coincided with the 14th of Muharram, it became known by this name. The operation was carried out in three phases and continued until mid-November. The main phases lasted from November 1st to November 9th, while sporadic clashes, defensive line adjustments, and local counterattacks continued until November 16th.[7]

At the beginning of the operation, Qaem Headquarters 1, 2, 3 and 4 engaged in the battle. In the first phase, Qaem 1, under the command of Ahmad Kazemi, started its mission on the northern, southern, and central fronts. The forces managed to penetrate Iraq’s fortified defensive lines, which were filled with minefields, barbed wire, and trenches. On the first front, the forces surrounded heights 298 and 292 and cleared part of the Hamrin Mountain range, capturing the heights overlooking Tayyib town and suppressing hills in the area with the help of the Qaem 3. Forces engaged in the second front captured and cleared the hills around Height 298, took several enemy soldiers as war prisoners, and destroyed their bunkers. Troops on the third front seized the mountains and hills of the area and stationed a battalion to secure the right flank in the west of the Mimeh River. On the southern flank of Qaem 1, Qaem 2 cleared the area, and Qaem 3 advanced from both the northern and southern fronts, achieving its objectives. The primary challenge was the southern front where Qaem 4 was engaged. Forces were supposed to advance from three sides—Cham-Sari in the north, Cham-Rabot at the center, and Cham-Hendi in the south. However, unexpected flooding and overflow caused by rising water levels in the Doyrej, Mimeh, and Chikhwab rivers, along with the deployment of Iraqi troops to the western flank of the river, halted the Iranian forces movement in Cham-Rabot and Cham-Hendi. Several troops of the Imam Sajjad (as) Battalion and Imam Hussain (as) Brigade were unable to cross the rivers. Their equipment, tents, ammunition, and weapons were submerged, and some soldiers drowned. The lack of communication routes and escape options, along with the psychological pressure, prevented the forces from fulfilling their objectives. Therefore, the commanders focused their efforts on the Cham-Sari front. After rebuilding the Doyrej Bridge, which had been destroyed by the enemy, the forces managed to cross it, capturing part of the Cham-Sari–Sharhani asphalt road and clearing areas around Heights 400.[8]

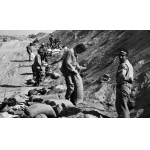

On the first day of the operation, over 500 square kilometers were liberated, including the key heights 400 and 298 and surrounding hills. Some 1,400 enemy soldiers were taken prisoner, and 9 Iraqi army brigades suffered 20 to 80 percent losses. In addition, 220 Iraqi tanks, armored personnel carriers, and vehicles were destroyed, and 145 light and heavy vehicles and a large number of ammunition were captured.[9]

The second phase of the operation began on November 3rd with Iranian forces launching attacks and inflicting heavy casualties on Iraqi units who tried to enter the area. Also, by establishing a defensive line, they reached the Zubeidat–Sharhani asphalt road and the Cham-Sari region towards the southwest and managed to place the western border regions up to 20 kilometers deep, along with the Basrah–al-Amarah–Baghdad supply and communication routes, under direct fire. The third phase began on November 7th, during which approximately 300 square kilometers were liberated, including the Zubeidat–Sharhani areas, the Abu Ghuraib Outpost, and oil facilities comprising 35 wells. In response, Iraq bombarded the whole liberated areas.

On November 8th, to complete the third phase, Iranian forces tried to close the gap between the 8th Najaf Ashraf and 25th Karbala brigades (Qaem 1 and 2) by reinforcing and stabilizing defensive lines. Due to depleted ammunition, delayed support, and Iraqi pressure, Qaem 4 was forced to withdraw from Height 175. However, this area was recaptured by Iranian forces on November 9th after the two armies fought and collided with each other several times.[10]

On November 10th and 11th, the Iranian forces mostly sought to stabilize and reinforce defensive positions. On November 12th, Iraq bombarded the Nahr Anbar area in an attempt to reclaim lost territory but retreated to 8 kilometers south of Cham-Hendi. This withdrawal resulted in 1,100 Iraqi casualties (killed and wounded), 46 war prisoners, and the destruction of 13 tanks and armored vehicles. In fact, it marked the conclusion of the primary phases of Operation Muharram, ending with a complete victory for Iranians and consolidation of the captured positions.[11]

Overall, the operation resulted in the liberation of approximately 1,000 square kilometers of Iranian territory, including heights 400, 175, and 298, the Bayat oil facility, Nahr Anbar, Pol and outposts in Cham-Sari, Musian, and Rabot on Iranian soil, as well as Sharhani, Abu Ghuraib, Hamad Shahab, and Bajileh in Iraq. Moreover, the Ain-Khosh–Dehloran Road was secured from enemy fire, and Iraq’s Tayyib town came under Iranian observation. More than 6,000 Iraqi troops were killed or wounded, and 2,300 were captured. Also, 10 Iraqi brigades and 3 armored and mechanized battalions lost 50 to 100 percent of their combat power.[12]

It is worth mentioning that Iraq used chemical and toxic gases during this operation; however, due to weather conditions, including wind and rain, their effects were minimal.[13]

Following its defeat in Operation Muharram, Iraq resumed bombing the operational area and attacking Iranian oil terminals in Khark, as well as cities such as Abadan, Khorramshahr, and Ilam.[14]

After Operation Muharram, the responsibility for defending the area from the Abu Ghuraib Outpost to the Zubeidat junction was assigned to the 1st Brigade of the 21st Infantry Division of the Army. In early 1983, the War Command Headquarters planned Operation Valfajr 1 to clear the Hamrin Heights in northern Fakkeh, which was carried out in April 1983.[15]

Approximately 700 troops who had been deployed from Isfahan were martyred in this operation. On November 16, 1982, the people of Isfahan held funeral processions for 370 martyrs, and a few days later for another 250 martyrs. In a message, Imam Khomeini (ra) praised the people of Isfahan, and subsequently, this date was marked as the “Day of Epic and Self-Sacrifice of the People of Isfahan”.[16]

On March 21, 2002, the bodies of five anonymous martyrs from the 14th Imam Hussain (as) Division, who had been martyred in Operation Muharram, were buried at the Martyrs’ Cemetery in Dehloran. On this occasion, the “Memorial of the Anonymous Martyrs” was erected at the site. Furthermore, the Haft-Dahane Bridge over the Doyrej River was renamed the “Muharram Martyrs”.[17]

[1] Dorudian, Muhammad, Seyri dar Jang-e Iran va Araq, Vol. 2: Khorramshahr ta Faw (A Review of Iran-Iraq War, Vol. 2: From Khorramshahr to Faw), Tehran: Sepah-e Pasdaran-e Enqelab-e Eslami, Markaz-e Asnad va Tahqiqat-e Defa-e Muqaddas, 1999, Pp. 42–48; Razaghzadeh, Amir, Atlas-e Rahnama 3: Ilam dar Jang (Atlas 3: Ilam in the War), Tehran: Sepah-e Pasdaran-e Enqelab-e Eslami, Markaz-e Asnad va Tahqiqat-e Defa-e Muqaddas, 2001, p. 70; Lotfi, Muhammad Hasan, Hussaini, Seyyed Yaqoub, Artesh-e Jomhuri-ye Eslami-ye Iran dar Hasht Sal-e Defa-e Muqaddas, Vol. 6: Amaliyyat-e Ramazan va Muharram (The Islamic Republic of Iran Army during the Eight Years of Sacred Defense, Vol. 6: Operations Ramazan and Muharram), Tehran: Sazman-e Aqidati-Siasi Artesh-e Jomhuri-ye Eslami-ye Iran, 1997, Pp. 117–118.

[2] Lotfollahzadegan, Alireza, Roozshomar-e Jang-e Iran va Araq, Ketab-e Bist-o Yekom: Amaliyyat-e Moslem ibn Aqil (Chronology of Iran-Iraq War, Book 21: Operation Moslem ibn Aqil), Tehran: Sepah-e Pasdaran-e Enqelab-e Eslami, Markaz-e Asnad va Tahqiqat-e Defa-e Muqaddas, 2012, p. 843.

[3] Ibid., p. 22; Lotfollahzadegan, Alireza, Roozshomar-e Jang-e Iran va Araq, Ketab-e Bist-o Dovvom: Amaliyyat-e Muharram (Chronology of Iran-Iraq War, Book 22: Operation Muharram), Tehran: Sepah-e Pasdaran-e Enqelab-e Eslami, Markaz-e Asnad va Tahqiqat-e Defa-e Muqaddas, 2014, p. 17; Rashid, Mohsen, Atlas-e Jang-e Iran va Araq (Atlas of Iran-Iraq War), p. 69.

[4] Lotfollahzadegan, Alireza, Roozshomar-e Jang-e Iran va Araq, Ketab-e Bist-o Yekom (Chronology of Iran-Iraq War, Book 21), p. 843; Lotfollahzadegan, Alireza, Roozshomar-e Jang-e Iran va Araq, Ketab-e Bist-o Dovvom (Chronology of Iran-Iraq War, Book 22), p. 17; Dorudian, Muhammad, Seyri dar Jang-e Iran va Araq (A Review of Iran-Iraq War), Vol. 2, p. 119; Poorjabbari, Pejman, Atlas-e Joghrafia-ye Hamasi 2: Ilam dar Jang (Epic Geography Atlas 2: Ilam in the War), Tehran: Bonyad-e Hefaz-e Asar va Nashr-e Arzeshha-ye Defa-e Muqaddas, 2015, p. 168; Lotfi, Muhammad Hasan, Hussaini, Seyyed Yaqoub, Artesh-e Jomhuri-ye Eslami-ye Iran dar Hasht Sal-e Defa-e Muqaddas (The Islamic Republic of Iran Army during the Eight Years of Sacred Defense), Vol. 6, p. 119.

[5] Lotfollahzadegan, Alireza, Roozshomar-e Jang-e Iran va Araq, Ketab-e Bist-o Dovvom (Chronology of the Iran-Iraq War: Book 22), Pp. 17–18; Poorjabbari, Pejman, Atlas-e Joghrafia-ye Hamasi 2 (Epic Geography Atlas 2), Pp. 168–169.

[6] Lotfi, Muhammad Hasan, Hussaini, Seyyed Yaqoub, Artesh-e Jomhuri-ye Eslami-ye Iran dar Hasht Sal-e Defa-e Muqaddas (The Islamic Republic of Iran Army during the Eight Years of Sacred Defense), Vol. 6, p. 119.

[7] Lotfollahzadegan, Alireza, Roozshomar-e Jang-e Iran va Araq, Ketab-e Bist-o Dovvom, Pp. 17–18, 186–187; Poorjabbari, Pejman, Atlas-e Joghrāfiā-ye Hamāsi 2, p. 168.

[8] Lotfollahzadegan, Alireza, Roozshomar-e Jang-e Iran va Araq, Ketab-e Bist-o Dovvom (Chronology of the Iran-Iraq War: Book 22), Pp. 188–190, 213–215; Poorjabbari, Pejman, Atlas-e Joghrafia-ye Hamasi 2 (Epic Geography Atlas 2), p. 170; Rashid, Mohsen, Atlas-e Jang-e Iran va Araq (Chronology of the Iran-Iraq War), p. 69.

[9] Lotfollahzadegan, Alireza, Roozshomar-e Jang-e Iran va Araq, Ketab-e Bist-o Dovvom (Chronology of Iran-Iraq War: Book 22), p. 217.

[10] Ibid., Pp. 19, 308–309, 313, 335, 350.

[11] Ibid., Pp. 20, 302, 377, 390, 401–402.

[12] Rashid, Mohsen, Atlas-e Jang-e Iran va Araq (Chronology of Iran-Iraq War), p. 69; Dorudian, Muhammad, Seyri dar Jang-e Iran va Araq (A Review of Iran-Iraq War), Vol. 2: Khorramshahr ta Faw, p. 44; Lotfollahzadegan, Alireza, Roozshomar-e Jang-e Iran va Araq, Ketab-e Bist-o Dovvom (Chronology of Iran-Iraq War: Book 22), p. 402.

[13] Rooznameh-ye Jomhouri-ye Eslami (Jomhouri Eslami Newspaper), No. 1004, 17 November 1982, Pp. 1, 4.

[14] Lotfollahzadegan, Alireza, Roozshomar-e Jang-e Iran va Araq, Ketab-e Bist-o Dovvom (Chronology of Iran-Iraq War: Book 22), p. 428.

[15] Lotfi, Muhammad Hasan, Hussaini, Seyyed Yaqoub, Artesh-e Jomhuri-ye Eslami-ye Iran dar Hasht Sal-e Defa-e Muqaddas (The Islamic Republic of Iran Army during Eight Years of Sacred Defense), Vol. 6, p. 159.

[16] Rooznameh-ye Keyhan (Keyhan Newspaper), No. 19796, 21 November 2010, p. 11; Rooznameh-ye Keyhan (Keyhan Newspaper), No. 20925, 19 November 2014, p. 7.

[17] Poorjabbari, Pejman, Atlas-e Joghrafia-ye Hamasi 2 (Epic Geography Atlas 2), Pp. 162, 173–174.