Battles

Operation Valfajr 1

Leila Heydari Bateni

260 Views

Operation Valfajr 1 was launched in April 1983 under the command of the Islamic Republic of Iran Army in southern Iran. The main goal was to take control of the Hamrin Heights and push the Iraqi army back from occupied areas. However, despite breaking through the Iraqi defensive lines, the Iranians failed to consolidate their positions.

The failure of Operation Preliminary Valfajr in February 1983 led to the planning of a new attack.[1] Less than two months later, in a meeting of the Supreme Defense Council, Colonel Ali Sayyad Shirazi, Commander of the Islamic Republic of Iran Army Ground Forces, was tasked with presenting the final plan for the new operation.[2] The new plan identified the northern areas of Fakkeh as the target location[3] and chose the slogan “fire instead of blood” for the operation.[4] In fact, Operation Valfajr 1 was a continuation of Operation Muharram (November 1982) and Operation Preliminary Valfajr.[5]

The operational area was bounded to the north by the Zubeidat and the Bajalyah Valley in the Hamrin Heights (Iraq), to the south by the southern areas of the Doiraj River and the Pichangizah border outpost near northern Fakkeh, to the east by the Doiraj River in Iran, and to the west by the Tayyeb River in Iraq. Main objectives included capturing the Hamrin and Jabal Foqi heights, gaining control over the region’s plains, pushing enemy forces out of northern Fakkeh and the eastern banks of the Doiraj River, advancing towards al-Amarah, capturing the Ghazileh Bridge, and enabling the forces to make extensive, concentrated use of artillery fire.[6]

The joint Operation Valfajr1 was carried out under the command of the Army, with units from the Karbala and Najaf headquarters of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and several Army divisions participating.

Karbala Headquarters comprised the 41st Tharallah (as), 7th Vali Asr (as), 8th Najaf, 19th Fajr, and 14th Imam Hussain (as) divisions, in addition to the 33rd al-Mahdi (as) Brigade.

Najaf Headquarters included the 31st Ashura, 27th Muhammad Rasulullah (pbuh), and 5th Nasr divisions, along with the 10th Seyyed al-Shuhada (as) Brigade.

Also, the 55th Airborne, 84th Khorramabad, 58th Zulfaqar, and 37th Shiraz Armored brigades, as well as the 21st Hamzeh Division, and the 2nd Brigade of the 77th Khorasan Division were the Army units engaged in the operation.[7]

The Khatam al-Anbiya (pbuh) Headquarters served as the joint command that issued the attack order on April 10, 1983, with the code name “Ya Allah, Ya Allah, Ya Allah”. The operation officially ended on April 17th.[8]

The operation began at 11 PM with heavy artillery fire. On the right (northern) flank, Karbala Headquarters was tasked with carrying out an offensive. On the left (southern) flank, the units including Najaf Headquarters and Army forces led by Army Colonel Manoochehr Dezhkam and IRGC commander Muhammad Ebrahim Hemmat had to take defensive positions.[9] The Bajalyah Valley marked the central axis between the two headquarters. Artillery support came from 14 Army artillery battalions, and 4 IRGC artillery battalions, and air support was provided by the Army Air Force.[10]

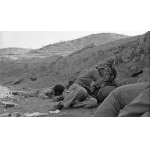

Despite early advances on both flanks and capturing some heights, the units engaged on the central front failed to penetrate the Iraqi positions thus the gains were not consolidated. A lack of coordination also caused delays in the Iranians pushing forward.[11] As a result, one of the key heights could not be captured due to extensive minefields and barriers[12], and the operation was halted.

On the southern front, the Najaf Headquarters was tasked with crossing the Doiraj River. In the early hours, one battalion managed to reach its target near the Pichangizah Post. Some battalions also breached the first and second Iraqi defense lines after clearing minefields in the central area.[13] Although parts of the Iranian forces reached their phase-one objectives on the flanks, strong enemy resistance and heavy obstacles in the center meant limited success.[14] Finally, on the morning of the second day, a withdrawal order was issued.

The second phase began on April 12th. The control of several heights shifted back and forth between the two sides multiple times within just a few days.[15] Therefore, the units focused on defending positions, exchanging fire, and repelling Iraqi counterattacks. In the following days, the Iranian fighters, while facing hand-to-hand combat and increasing enemy pressure and resistance, began reinforcing and reorganizing their positions.[16]

Sixty thousand shells were fired by Iran during the operation—a record for the entire war. Although carried out in multiple phases and directions and Iranian forces could break through enemy defensive lines, the captured positions could not be held due to Iraqis’ combat readiness and the disorganization of the Iranian units.[17]

In this operation, over 4000 Iraqi soldiers were killed or wounded, and 350 captured. Several helicopters, tanks, and vehicles were destroyed, while 50 tanks/armored personal carriers and 200 vehicles were seized. Iranian forces lost about 1000 men, with many wounded (5000), some missing, and over 100 captured.[18] Reza Cheraghi, commander of the 27th Muhammad Rasulullah (pbuh) Division, was among the martyrs.[19]

The disagreement among commanders led to the establishment of two separate headquarters for the Army and the IRGC, both of which conducted independent operations—one of the reasons for the operation’s failure. Other contributing factors included darkness, troop fatigue, the limited capability of Iran’s infantry, Iraq’s strong defensive positions, heavy artillery fire, and the upper hand in having control of the heights.[20] Furthermore, a lack of skilled personnel and trained commanders, poor infantry training, insufficient information about the Iraqi army, and changes in operational planning also caused the failure of the operation.[21]

Following the failure of several minor operations, western Iran became the center of attention, and thus Operation Valfajr 2 was launched on July 20, 1983, near Piranshahr.[22]

[1] Jafari, Mojtaba, Atlas-e Nabardha-ye Mandegar (Atlas of Enduring Battles), Tehran: Soreh Sabz, 35th ed., 1393, p. 88.

[2] Rashid, Mohsen, Atlas-e Jang Iran va Araq (Atlas of the Iran-Iraq War), Tehran: Markaz-e Motaleat va Tahqiqaat-e Jang, 2nd ed., 1389, p. 71.

[3] Shirali-Niya, Jafar, Zahedi, Saeed, Ketab-e Rawi, Vol. 8: Ravayat-e Fakkeh, Qomqomehaye Teshneh (The Narrator’s Book, Vol. 8: The Story of Fakkeh, Thirsty Canteens), Tehran: Ideh No, 1388, p. 81; Ardestani, Hussain, Tajzieh va Tahlil-e Jang Iran va Araq, Vol. 3: Tanbih-e Motajavez (Analysis of the Iran-Iraq War, Vol. 3: Punishing the Aggressor), Tehran: Markaz-e Motaleat va Tahqiqaat-e Jang, 1379, p. 47.

[4] Ardestani, Hussain, Tajzieh va Tahlil-e Jang Iran va Araq (Analysis of the Iran-Iraq War), Vol. 3, p. 49.

[5] Behroozi, Farhad, Taqvim-e Tarikh-e Defa Muqaddas, Vol. 32: Dar Emtedad-e Fajr (Calendar of Sacred Defense History, Vol. 32: In the Continuum of Dawn), Tehran: Markaz-e Asnad-e Enqelab-e Eslami, 1395, p. 678.

[6] Shirali-Niya, Jafar, Zahedi, Saeed, Ketab-e Rawi (The Narrator’s Book), Vol. 8, p. 82; Ardestani, Hussain, Tajzieh va Tahlil-e Jang Iran va Araq (Analysis of the Iran-Iraq War), Vol. 3, p. 48; Behroozi, Farhad, Taqvim-e Tarikh-e Defa Muqaddas (Calendar of Sacred Defense History), Vol. 32, Pp. 698-678; Foroudi, Qasem, Atlas-e Manateq-e Amaliati-ye Gharb va Jonub-e Gharb (Atlas of Operational Areas in the West and Southwest), Tehran: Bonyad-e Hefz-e Asaar va Nashr-e Arzesh-ha-ye Defa Muqaddas, 1395, p. 90.

[7] Shirali-Niya, Jafar, Zahedi, Saeed, Ketab-e Rawi (The Narrator’s Book), Vol. 8, p. 83; Ardestani, Hussain, Tajzieh va Tahlil-e Jang Iran va Araq (Analysis of the Iran-Iraq War), Vol. 3, Pp. 50-51.

[8] Jafari, Mojtaba, Atlas-e Nabardha-ye Mandegar (Atlas of Enduring Battles), p. 88.

[9] Behroozi, Farhad, Taqvim-e Tarikh-e Defa Muqaddas (Calendar of Sacred Defense History), Vol. 32, p. 713.

[10] Foroudi, Qasem, Atlas-e Manateq-e Amaliati-ye Gharb va Jonub-e Gharb (Atlas of Operational Areas in the West and Southwest), Pp. 92-93.

[11] Ibid., p. 94; Behroozi, Farhad, Taqvim-e Tarikh-e Defa Muqaddas (Calendar of Sacred Defense History), Vol. 32, Pp. 710-711.

[12] Foroudi, Qasem, Atlas-e Manateq-e Amaliati-ye Gharb va Jonub-e Gharb (Atlas of Operational Areas in the West and Southwest), p. 94.

[13] Behroozi, Farhad, Taqvim-e Tarikh-e Defa Muqaddas (Calendar of Sacred Defense History), Vol. 32, p. 715.

[14] Ibid., p. 766.

[15] Foroudi, Qasem, Atlas-e Manateq-e Amaliati-ye Gharb va Jonub-e Gharb (Atlas of Operational Areas in the West and Southwest), p. 94.

[16] Ibid., Pp. 1209-1204.

[17] Rashid, Mohsen, Atlas-e Jang Iran va Araq (Atlas of Iran-Iraq War), p. 71.

[18] Ardestani, Hussain, Tajzieh va Tahlil-e Jang Iran va Araq (Analysis of the Iran-Iraq War), Vol. 3, p. 54; Jafari, Mojtaba, Atlas-e Nabardha-ye Mandegar (Atlas of Enduring Battles), p. 88.

[19] Babaei, Gol-Ali, Raz-e Aan Setareh (The Secret of That Star), Vol. 3 of Majmooeh-ye 27 Dar 27, Tehran: Saiqeh, 1391, Pp. 121-122.

[20] Shirali-Niya, Jafar, Zahedi, Saeed, Ketab-e Rawi (The Narrator’s Book), Vol. 8, p. 83; Ardestani, Hussain, Tajzieh va Tahlil-e Jang Iran va Araq (Analysis of the Iran-Iraq War), Vol. 3, p. 54.

[21] Behroozi, Farhad, Taqvim-e Tarikh-e Defa Muqaddas (Calendar of Sacred Defense History), Vol. 32, p. 1209.

[22] Doroudian, Muhammad, Siri Dar Jang Iran va Araq, Vol. 6: Aghaz ta Payan (A Journey through the Iran-Iraq War, Vol. 6: From Beginning to End), Tehran: Markaz-e Motaleat va Tahqiqaat-e Jang Sepah, 1376, p. 79.