Battles

Operation Farmande Koll-e Qova

Leila Azadeh

162 Views

On June 11, 1981, the limited offensive operation known as Farmande Koll-e Qova, Khomeini Ruhollah (ra), was carried out under the command of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) in the eastern Karun region and south of Darkhovein, aiming to push enemy forces back to the west of Karun.

The operation coincided with the dismissal of Bani-Sadr, the then-President of Iran, as Commander-in-Chief. Therefore, given Iran’s political situation and the operational area, this operation was so important and could serve as a preliminary step to breaking the siege of Abadan.

After some operations were launched in Shush, no significant movements had taken place on the southern front, and the Iranian commanders were mostly busy analyzing areas and finding a way to launch a special military operation. Among the potential targets, the Abadan front and breaking its siege were of particular importance. With the continued siege of Abadan, which was about to fall, Iraq could threaten Mahshahr and Imam Khomeini (ra) ports. Following Imam Khomeini’s historic command to break the siege of Abadan, measures were taken to push Iraqi forces back to the west of Karun. Although these efforts did not fully succeed, they prevented the Iraqis from advancing further into Abadan.[1]

The forces on the Darkhovein front had been preparing for approximately six months to launch the operation. Necessary studies were conducted to identify the position of Iraqi forces and plan the operation. During this operation, the Iranian forces advanced towards the Qasba and Mared bridges over the Karun River, north of Abadan, as part of the main plan for breaking the siege of Abadan.[2]

The suitable ground connection between the Darkhovein front and Ahvaz led the enemy to focus on its northern flank, strengthening its defensive lines and launching multiple attacks in this area.[3]

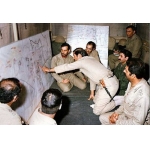

The preliminary preparations for the operation began in early 1981. As the operation was going to be launched in a plain area, the commander (Mahmoud Pahlavannejad) ordered that a hidden canal be dug out.[4] However, since the Iraqis could easily see the machines digging the canal, most of the project was done during the nights by IRGC forces with shovels, pickaxes, and other light equipment over three months. The canal extended from the south of Muhammadieh (south of Darkhovein) to within 250 meters of Iraqi positions, covering a length of 1,750 meters. After completing the canal, the operation plan was prepared in collaboration with the 77th Infantry Division Headquarters and the commander of the IRGC in Darkhovein, Hussain Kharrazi.[5] One day before the operation, Yahya Rahim Safavi, the IRGC commander of the operation, announced that the attack would begin on June 11th to push the enemy forces back to the Mared Bridge.[6] Before the operation, Ayatollah Seyyed Muhammad Hussaini Beheshti, the then-Chief Justice of Iran, visited the area and made a speech to boost the fighters’ morale.[7]

Finally, as planned by Rahim Safavi and Hassan Baqeri, the operation began at 3:30 AM on June 11, 1981, from three directions under the command of Hussein Kharrazi.[8] Supported by an Army artillery battery, a total of 350 IRGC and Basij forces engaged in the operation. Also, a tank company from the 214th Battalion of the 77th Infantry Division served as a reserve force.[9] Organized into three companies, each comprising three squads of 23 soldiers and a 15-member logistics group responsible for providing ammunition and transporting prisoners, casualties, and martyrs, the Iranian forces attacked the enemy. The attack was carried out on three axes, namely the eastern Karun River led by Reza Rezaei, the central canal route led by Mahmoud Pahlavannejad, and the eastern Ahvaz-Abadan Road led by Mansour Movahedi.[10] Advancing towards the positions of Iraq’s Salah al-Din Armored Battalion, part of the 8th Mechanized Brigade, the Iranian forces captured the first three defensive berms of the Iraqi 3rd Armored Division.[11] As a result, they consolidated their position and neutralized enemy counterattacks by relying on a defensive berm that had been constructed on the first night of the operation.[12] With the efforts and determination of Muhammad Tarhchi, commander of the Logistics Unit of Jahad-e Sazandegi Organization, for the first time, a three-kilometer defensive berm was built overnight amid the enemy’s counterattacks to secure the newly captured area.[13]

Due to the strategic importance of Darkhovein, the Iraqi army had deployed 1,400 infantry troops, 500 special forces, and 65 tanks and armored personnel carriers to that area.[14] Supported by Army artillery, the Iranian forces advanced two kilometers into Iraqi positions, capturing 250 enemy soldiers. In addition, 12 tanks and 3 armored personnel carriers, along with 3 entire Iraqi battalions, were destroyed, resulting in over 200 casualties and injuries among the enemy forces.[15] 15 Iraqi tanks and armored vehicles were seized, by the use of which the IRGC’s Armored Unit was formed. During this operation, 100 IRGC forces (from Isfahan and Qom) were martyred, and 150 were wounded.[16] The operation led to the liberation of approximately 4 square kilometers of occupied area in southern Salmaniyeh, bringing the front line closer to the Mared Bridge. Consequently, Iraq dismantled the bridge and instead used the Qasba and later Haffar bridges.[17]

The outcomes of this operation completely changed Iraqis’ calculations and estimations about Iran’s military capabilities and exposed the enemy’s vulnerabilities. On the other hand, it enhanced Iranians’ confidence in employing innovative combat tactics, facilitated the cooperation between the Army, IRGC, and Jahad-e Sazandegi Organization, and fostered the recognition of revolutionary forces within the conventional military structure.[18]

[1] Jafari, Mojtabi, Atlas-e Nabardha-ye Mandegar (Atlas of Memorable Battles), Tehran: Sureh Sabz, 22nd Edition, 1391, p. 54.

[2] Alaei, Hussain, Tarikh-e Tahilii-ye Jang-e Iran va Araq (Analytical History of the Iran-Iraq War), Vol. 1, Tehran: Marz-o-Boom, 1395, p. 326.

[3] Farudi, Qasem, Atlas-e Mantaqeha-ye Amaliyati-ye Gharb va Jonub-Gharb (Atlas of Operational Areas in the West and Southwest), Tehran: Bonyad-e Hefz-e Asar va Nashr-e Arzesh-ha-ye Defa-e Muqaddas, 1395, p. 19.

[4] Hussaini, Yaqub, Javadipour, Muhammad, Artesh-e Jomhouri-ye Eslami-ye Iran dar Hasht Sal-e Defa-e Muqaddas (The Islamic Republic of Iran Army in the Eight Years of Sacred Defense), Vol. 3: Eshghal-e Khorramshahr va Shekastan-e Hasr-e Abadan (The Occupation of Khorramshahr and Breaking the Siege of Abadan), Tehran: Sazman-e Aqidati Siasi-ye Artesh-e Jomhouri-ye Eslami-ye Iran, 1373, p. 230; Bani-Lohi, Seyyed Ali, Muradpiri, Hadi, Nabardha-ye Sharq-e Karun be Ravayat-e Farmandehan (Battles of East Karun as Narrated by Commanders), Tehran: Markaz-e Asnad-e Defa-e Muqaddas-e Sepah-e Pasdaran-e Enghlab-e Eslami, 4th Edition, 1387, p. 147.

[5] Habibi, Abolqasem, Atlas-e Rahnamay-e 6: Abadan dar Jang (Atlas 6: Abadan in the War), Tehran: Markaz-e Motaleat va Tahqiqat-e Jang-e Sepah-e Pasdaran-e Enqelab-e Eslami, 1382, p. 105; Hamaseh-ye Darkhovein (The Epic of Darkhovein), Isfahan: Sepah-e Pasdaran-e Enqelab-e Eslami, 1361, p. 41.

[6] Alaei, Hussain, Tarikh-e Tahilii-ye Jang-e Iran va Iraq, Vol. 1, p. 327; Safavi, Seyyed Rahim, Ruzha-ye Moqavemat (Days of Resistance), Vakavi-ye Amaliyat-e Darkhovein va Shekast-e Hasr-e Abadan (Analysis of the Darkhovein Operation and Breaking the Siege of Abadan), Qom: Nashr-e Hoda, 1390, p. 51.

[7] Habibi, Abolqasem, Atlas-e Rahnamay-e 6 (Atlas 6), Pp. 106 and 107.

[8] Hamaseh-ye Darkhovein, Pp. 44 and 45; Bani-Lohi, Seyyed Ali, Muradpiri, Hadi, Nabardha-ye Sharq-e Karun be Ravayat-e Farmandehan, p. 153.

[9] Alaei, Hussain, Tarikh-e Tahilii-ye Jang-e Aran va Iraq (Analytical History of the Iran-Iraq War), Vol. 1, p. 327.

[10] Habibi, Abolqasem, Atlas-e Rahnamay-e 6 (Atlas 6), Pp. 106 and 107.

[11] Dary, Hassan, Atlas-e Rahnamay-e 5: Karnameh-ye Nabardha-ye Zamini (Atlas 5: Record of Ground Battles), Tehran: Markaz-e Motaleat va Tahqiqat-e Jang-e Sepah-e Pasdaran-e Enqelab-e Eslami, 1381, p. 77.

[12] Alaei, Hussain, Tarikh-e Tahilii-ye Jang-e Iran va Araq (Analytical History of the Iran-Iraq War), Vol. 1, p. 327; Safavi, Seyyed Rahim, Ruzha-ye Moqavemat (Days of Resistance), p. 52.

[13] Samiei, Ali, Karnameh-ye Towsifi-ye Amaliyat-e Razmandegan-e Eslam dar Tool-e Hasht Sal-e Defa-e Muqaddas (Descriptive Record of the Operations of Islamic Warriors During the Eight Years of Sacred Defense), Tehran: Namayandegi-ye Vali-Faqih dar Niroo-ye Zamini, Moavenat-e Tablighat va Entesharat, 1376, Pp. 38 and 39.

[14] Dorudian, Muhammad, Tajziyeh va Tahili-e Jang-e Iran va Araq (Analysis of the Iran-Iraq War), Vol. 2: Jang; Bazyabi-ye Sobat (War; Regaining Stability), Tehran: Markaz-e Motaleat va Tahqiqat-e Jang-e Sepah-e Pasdaran-e Enqelab-e Eslami, 3rd Edition, 1384, p. 142.

[15] Alaei, Hussain, Tarikh-e Tahilii-ye Jang-e Iran va Araq (Analytical History of the Iran-Iraq War), Vol. 1, p. 327.

[16] Jafari, Mojtabi, Atlas-e Nabardha-ye Mandegar (Atlas of Memorable Battles), p. 54.

[17] Habibi, Abolqasem, Atlas-e Rahnamay-e 6 (Atlas 6), Pp. 106 and 107.

[18] Dorudian, Muhammad, Siri dar Jang-e Iran va Araq (A Journey Through the Iran-Iraq War), Vol. 1: Khunin-Shahr ta Khorramshahr (From Khunin-Shahr to Khorramshahr), Tehran: Markaz-e Motaleat va Tahqiqat-e Jang-e Sepah-e Pasdaran-e Enqelab-e Eslami, 4th Edition, 1377, p. 72.