Battles

Operation Muhammad Rasulullah (pbuh)

Leila Heydari Bateni

222 Views

Operation Muhammad Rasulullah (pbuh) took place in January 1982, under the joint command of the Islamic Republic of Iran Army and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), on the northwestern fronts (Kermanshah and Kurdistan provinces). It aimed at clearing and securing the international borders in Uramanat and Nosoud. Overall, the operation was successfully completed.

After the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War on September 22, 1980, Iraq initially occupied parts of Iran’s western and southern provinces and concentrated most of its military force in these areas. However, the widespread presence and active engagement of anti-revolutionary forces in the Kurdish regions of northwestern Iran, along with their acts of sabotage which distracted the Iranian military commanders and troops from focusing on foreign attacks, provided Iraq with secure conditions along the borders. After anti-revolutionary elements were pushed back to the Iraqi border, Iraq focused more on the northwest to retain Kirkuk, its third most important city, and maintain access to shared borders. Thus, in the winter of 1981, Iraq seized parts of Iran’s land borders from Nosoud to Marivan. Later on in the summer, eastern Nosoud was liberated during Operation Ruhullah. To liberate other parts of this region and establish a front in the northwest, which would cut off the connection between Iraqi troops in the south to their counterparts in the north, Operation Muhammad Rasulullah (pbuh) was devised.[1]

This operation was critical as it served as a supportive action for Operation Tariq al-Quds (capturing Bostan, November-December 1981), distracting the enemy troops, and disrupting their military formations.[2]

Muhammad Ebrahim Hemmat, commander of the Paveh IRGC, and Ahmad Motevaselian, commander of the Marivan IRGC, initially presented the preliminary plan for Operation Muhammad Rasulullah (pbuh) under the name Karbala 10.[3] The reconnaissance of the operational area was conducted in late 1981 by a special intelligence team led by Abbas Karimi.[4]

The area covered by Operation Muhammad Rasulullah (pbuh) included Marivan and Paveh, a vast region in the southwest of Kurdistan Province and the northwest of Kermanshah Province. This area is bounded to the north by Shiler Plain, located northeast of the Quch Soltan Heights; to the east by the Marivan front between the Dalani and Kamanjir heights up to the Panj-Qolleh, and to the south by the northern heights of the Nosoud border region, from Panj-Qolleh down to the south of Shushmi Heights. In addition, the operation covered the southern border heights of Takht-e Uramanat in Kurdistan, including the Iraqi towns of Beyareh and Tuwileh.

The objective of the operation was to clear the entire area of anti-revolutionary groups along the western borders of Uramanat, Nosoud, and Marivan, secure the routes, and control the activities in Iraqi border towns.[5]

The semi-large-scale Operation Muhammad Rasulullah (pbuh) was launched under the joint command of the IRGC and the Army at 6:30 AM on January 2, 1982, with the code-name “La ilaha illallah Muhammad Rasulullah (pbuh)” on two main fronts and was concluded at 4 PM the following day.[6]

The operation began along two primary fronts—Marivan and Paveh—as well as several secondary ones. The forces engaged in Marivan under the command of Haj Ahmad Motevaselian, were tasked with capturing and securing the Shangado, Panj-Qolleh, Darreh Tarik, Janbazan, and Pashgheleh heights as well as the city of Tuwileh. On Paveh front, Ebrahim Hemmat and his unit were responsible for clearing the town of Nosoud, the Kol Herat, Souni, and Shushmi mountains, as well as several villages of enemy forces, anti-revolutionary elements, and Iraqi troops, and then advancing towards Tuwileh.

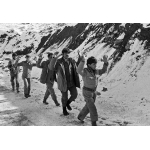

The Iranian forces on the northern front (Shushmi–Tuwileh) which included the eastern flank of Panj-Qolleh and the southern slopes of Kol Herat and Souni Herat, hiked the snow-covered mountains for several hours before clearing the western slopes of Shushmi Heights. They rapidly advanced to capture the strategically significant heights including Kol Herat, Suni Herat, Pashgheleh, and Kamar Siah, located west of Nosoud.

If the forces engaged on the southern front could successfully cut off the rear of Tuwileh, their counterparts would enter the town and destroy enemy positions. Consequently, two battalions from the Marivan IRGC, under Ahmad Motevaselian’s command, along with some units from Battalion 139 and the Khorramabad Infantry Brigade, continued advancing along the Takht-e Uramanat Heights towards Hani-Garmaleh and the border heights. However, delays in the arrival of a group of forces to the battlefield hindered the operation, resulting in only partial achievement of objectives. Moreover, the newly captured areas could not be stabilized due to enemy forces maintaining positions on mountains overlooking the Iranian troops.[7]

On the southern front (Panj-Qolleh – Tawer/Tarik Valley), the joint battalion, commanded by Muhammad Abdi, walked down the Panj-Qolleh and penetrated the Tawer Valley. After clearing the area, they advanced westward to reach the city of Tuwileh, in an attempt to cut off the rear supply routes of the city. Simultaneously, another joint battalion under the command of Hussain Qajehie was tasked with advancing through Tawer Valley towards the city of Biyareh, to attack the tactical headquarters of Iraq’s 116th Mountain Infantry Brigade of the 7th Division.[8]

During the first few hours of the operation, the units succeeded in capturing thirteen out of the sixteen designated targets. Also, Tuwileh and Biyareh, along with several surrounding villages, were surrounded. However, according to Hussain Qajehie, the forces were eventually ordered to retreat due to certain unspecified issues.[9]

By the evening of January 2nd, with the units engaging in the northern front failing to achieve the objectives and link up the two fronts, the Iraqis carried out counterattacks on military roads. Therefore, due to a lack of adequate support for Iranian forces along these routes, the captured areas could not be consolidated and as a result, Iranian units were forced to withdraw, and the operation came to an end.[10]

Four days later, in an interview with reporters from Payam-e Enqelab magazine, Muhammad Ebrahim Hemmat analyzed the operation, describing it as generally well-coordinated and successful. As he explained, the forces engaged in twelve fronts of which seven saw the defeat of Iraqi forces, and several occupied areas were liberated by Iranian troops who managed to advance as far as Tuwileh and succeeded in destroying three Iraqi tanks.[11]

Among those who sacrificed their lives during this operation were Muhammad Abdi, the commander of the second joint battalion of the Marivan IRGC, and his deputy, Ali Faraji.[12]

Hojatoleslam Hashemi Rafsanjani described the successful execution of the operation as the beginning of a new phase in the Sacred Defense. Highlighting its psychological impact on Iraq’s military and political command he noted that the operation demonstrated Iran’s capability to penetrate deep into enemy positions.[13]

The operation led to the closure of infiltration corridors used by anti-revolutionary elements, the clearing and securing of the border cities in the Uramanat region, and the liberation of the Tuwileh outpost and town, the Malgah and Peshgheleh heights, as well as the mountains located to the left of Iraq’s border post.

Other achievements included the complete destruction of Iraqi army bases surrounding Tuwileh, the death or injury of more than 1,000 Iraqi soldiers, and the capture of 191. Iranian forces also succeeded in destroying 10 artillery pieces, 50 vehicles of various types, and 4 Iraqi tanks and armored personnel carriers.[14]

One of the key features of this operation was the experience gained by commanders, which contributed to building military cadres in the following years. Ahmad Motevaselian and Muhammad Ebrahim Hemmat, the primary commanders of the operation, were subsequently appointed as commanders of the Muhammad Rasulullah (pbuh) Division in different periods. Another notable commander in this operation was Naser Kazemi, who served as the governor of Paveh.[15]

[1] Rashid, Mohsen, Atlas-e Jang-e Iran va Araq (Atlas of the Iran-Iraq War), Tehran: Markaz-e Motaleat va Tahqiqat-e Jang-e Sepah, 2010, p. 57; Jafari, Mojtaba, Atlas-e Nabardhaye Mandegar (Atlas of the Enduring Battles), Tehran: Novid Tarahan, 2004, p. 67.

[2] Behzad, Hussaini; Babaei, Gol-Ali, Hampay-e Saeqe (Alongside the Thunderbolt), p. 77 and 80.

[3] Ibid., p. 74.

[4] Ibid., p. 79.

[5] Ibid., p. 74; Rashid, Mohsen, Atlas-e Jang-e Iran va Araq (Atlas of the Iran-Iraq War), p. 57; Atlas-e Nabardhaye Mandegar (Atlas of the Enduring Battles), p. 67; Pourjaberi, Pejman, Atlas-e Joghrafiaye Hamasi, Vol. 3: Kermanshah dar Jang (Atlas of Epic Geography, Vol. 3: Kermanshah in War), Tehran: Bonyad Hefz Asar va Arzeshhaye Defa-e Muqaddas, 2013, p. 191.

[6] Jafari, Mojtaba, Atlas-e Nabardhaye Mandegar (Atlas of the Enduring Battles), p. 67; Pourjaberi, Pejman, Atlas-e Joghrafiaye Hamasi, Vol. 3, p. 191; Behzad, Hussaini; Babaei, Gol-Ali, Hampay-e Saeqe (Alongside the Thunderbolt), p. 111.

[7] Behzad, Hussaini; Babaei, Gol-Ali, Hampay-e Saeqe (Alongside the Thunderbolt), p. 94; Pourjaberi, Pejman, Atlas-e Joghrafiaye Hamasi (Atlas of Epic Geography), Vol. 3, p. 191.

[8] Behzad, Hussaini; Babaei, Gol-Ali, Hampay-e Saeqe (Alongside the Thunderbolt), p. 94.

[9] Ibid., p. 102.

[10] Pourjebari, Pejman, Atlas-e Joghrafiaye Hamasi (Atlas of Epic Geography), Vol. 3, p. 191.

[11] Behzad, Hussaini; Babaei, Gol-Ali, Hampay-e Saeqe (Alongside the Thunderbolt), p. 108.

[12] Ibid., p. 102.

[13] Hashemi, Yaser, Obour az Bohran, Karnama va Khaterehaye Sal-e 1360 Hashemi Rafsanjani (Passing through Crisis, Record and Memoirs of Hashemi Rafsanjani, 1981), Tehran: Daftar-e Nashr-e Maaref-e Enqelab-e Eslami, 1999, Pp. 429-430.

[14] Jafari, Mojtaba, Atlas-e Nabardhaye Mandegar (Atlas of the Enduring Battles), p. 67; Behzad, Hussaini; Babaei, Gol-Ali, Hampay-e Saeqe (Alongside the Thunderbolt), p. 108.

[15] Pourjaberi, Pejman, Atlas-e Joghrafiaye Hamasi (Atlas of Epic Geography), Vol. 3, p. 191.