Battles

Operation Ramazan

Leila Heydari Bateni

345 Views

In the summer of 1982, Operation Ramazan was carried out on the southern front, east of Basra in Iraq, under the joint command of the Islamic Republic of Iran Army and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

The objective of the operation was to penetrate into Iraqi territory to gain the upper hand and territorial advantages as Saddam sought to end the war under the pretext of Israel’s attack on southern Lebanon and retain control over Khorramshahr. Therefore, seizing enemy territory could lead to a fair resolution of the war, compelling Iraq to accept peace. However, the operation failed due to the lack of having enough information about the enemy’s positions.[1]

After the liberation of Khorramshahr, Iran adopted a new approach under the policy of “pursuing the aggressor” to turn the tide of war in its favor. Crossing the border and penetrating Iraqi territory up to the eastern bank of the Shatt al-Arab[2] led Iran to have control over the access routes to Basra. Subsequently, it was decided to follow the policy of pursuing the aggressor through another operation, creating more favorable conditions for Iran. By capturing parts of Iraqi territory, Iraq would have no choice but to accept peace or, at least, Iran would reinforce its position.[3]

On June 10, 1982, members of the Supreme Defense Council and key military commanders met with Imam Khomeini (ra). During this meeting, he emphasized that the Iranian forces should only enter into unpopulated or less-populated areas of the Iraqi territory. As a result, the operational plan was finalized on June 24th,[4] and since it was set to be executed on July 13, 1982, coinciding with the month of Ramazan, it was named Operation Ramazan.[5]

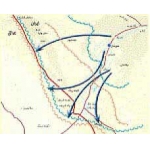

The operational area of Ramazan was a triangular-shaped terrain covering 1,600 square kilometers, bordered to the north by Koshk, Talaiyeh, and the southern edge of Hur al-Hoveyzeh, to the west by the Arvand River, and to the east by a north-south border line from Koshk to Shalamcheh.[6] This region also included areas west of the Ahvaz Road, north of the Fishing Canal, and northeast of Basra, Iraq.[7] In addition, the Shatt al-Arab River in Iraq, the Karun River in Iran, and the Hur al-Hoveyzeh were not only natural obstacles in that region but also formed part of the two countries’ shared border.[8]

Four headquarters (Quds, Fath, Nasr, and Fajr) affiliated with the ten IRGC brigades, two Army divisions, and one Army brigade, including the 16th and 92nd Armored Divisions, the units from the 21st and 77th Infantry Divisions, the 40th Infantry Brigade, the 22nd and 33rd Artillery Groups, three Army Aviation combat teams, as well as forces from the 1st, 3rd, 5th, and 7th Infantry Divisions, and units from the IRGC’s 30th Armored Division engaged in the operation led by the Karbala Operational Headquarters.[9]

Operation Ramazan began on July 13, 1982, at 9:30 PM with the code-name “Ya Mahdi (as)” on four axes, aiming to destroy Iraq’s Third Army Corps and secure the Arvand River. It had five phases and lasted until July 29, 1982. There were four bridges over Arvand River and Basra was located on its southwest, with significant political and military importance and well-equipped defensive systems.[10]

At the beginning of the operation, three headquarters launched attacks from three axes: two IRGC brigades and one Army brigade attacked the enemy from the northern flank. However, the obstacles and fortifications the enemy had made slowed down the Iranian forces’ advance. Despite initial progress in the northern Zaid outpost, which was the central axis of the region, they failed to capture Iraq’s triangular positions. In the southern axis and south of the Zaid outpost, four brigades rapidly bypassed obstacles, advancing 30 kilometers deep into Iraqi territory, reaching the Katiban Canal east of the Arvand and the Fishing Canal. They also destroyed the headquarters of Iraq’s 9th Armored Division and seized the command headquarters’ vehicle. However, the forces in the right flank could not fully defeat the enemy as the daylight came and the Iraqi reinforcements arrived.[11]

The second phase of the operation began on July 16th from the central axis south of the Zaid outpost, using the same combat forces engaged in the first phase along with an additional IRGC unit and two brigades under the command of the southern headquarters. The goal was to extend the forces’ advance to the Fishing Canal using the bridgehead captured in the first phase. Taking control of this area would reduce the distance to Basra to 12 kilometers. However, due to the reinforcement of the Iraqi army, the objective was not accomplished.

The third phase of the operation was launched on the central axis on July 21st, using the same forces as before along with three additional brigades, aiming to destroy Iraq’s armored equipment. Within the first few hours, the Iranian forces broke through enemy lines and destroyed or captured a significant portion of Iraqi equipment in an area covering 180 square kilometers. Two IRGC brigades and an Army unit initiated the fourth phase of the operation on July 23rd in Shalamcheh, but due to Iraqis’ combat readiness and the defensive obstacles in place, they were unable to achieve the objectives.

On July 28th, the last and fifth phase took place on the northern axis of the Zayd post, between the border fortifications of Iraq and the triangular-shaped berms of the post, with the cooperation of seven brigades from the IRGC and two brigades from the Army. The next day, operation commanders held a meeting at the Karbala Headquarters where it was decided that two battalions from the Najaf Brigade, along with the Imam Hussain (as) Brigade, keep moving northward, and two battalions from the Bethat Brigade replace Imam Hussain (as) Brigade as the force advancing southwards. While cleaning the western side of the region, the two forces would link up to reinforce their control over the captured areas. Moreover, the 1st and 2nd brigades of the 77th Division would support them from the north and south, suppressing Iraqi forces. However, this plan was not realized. As a result of a five-hour delay in the arrival of the Army forces, a strong response from the Iraqi army, the failure to link up the forces on the western side, daylight, and inattention to technical details in constructing the berms, the Iraqi forces managed to penetrate five kilometers into the area endangering the position of Iranian forces in the liberated areas. Therefore, the commanders who realized that it is unwise to keep the forces in the area, announced the end of the operation.[12]

Although the units of the Fath Headquarters managed to advance about fifteen kilometers into Iraqi territory up to the Katiban River and reach the headquarters of the Iraqi army command, they failed to stabilize their position due to the vulnerability of the right flank and the inability of the other headquarters to overcome obstacles. Therefore, the Fath Headquarters only captured the area around the Zaid post.[13] On the other hand, the forces were supposed to make up for the failures in earlier stages by constructing a large, high, double-layered berm on the eastern and western sides in the northern part of the region. However, due to a miscalculation, the main berm was connected to the fourth triangle instead of the third one, adding several kilometers to the width of the operational area and halting the success of the operation.[14]

On July 29, 1982, following heavy human casualties among the Iraqi army and the capture of three commanders during Operation Ramazan, the Iraqi government called up reserve soldiers for the second time.[15]

In this operation, the Army Aviation helicopter pilots transferred 690 wounded, carried out 961 helicopter landings and transported 10 tons of supplies by 34 helicopters and flying 629 hours.[16]

Operation Ramazan was the first large-scale, nationwide Iranian attack on Iraqi territory. Therefore, it was necessary to ensure its success with sufficient information, resources, and new tactics. However, the lack of satellite intelligence, aerial photography, and reliance on reconnaissance done by the forces had a negative impact on the operation’s execution, leading to its failure.[17]

The Iraqi army managed to defeat the Iranian forces by using new defense strategies and promoting a sense of Arab ethnicity among its soldiers.[18]

Colonel Ali Sayyad Shirazi, the then-commander of the Iranian Army Ground Forces, believed that weaknesses in the technical aspects of warfare and ideological matters were the causes of the operation’s failure. The failure to build the berm promptly and provide necessary reinforcements for the right flank at the Shalamcheh axis and the left flank at the flooded Bubiyan were some of the deficiencies in the technical aspects of warfare. Another reason was the lack of coordination between the Army and the IRGC.[19]

Also, in the view of the then-commander of the IRGC, Mohsen Rezaei, the operation faced failure because of the enemy’s fortifications on the right flank of the region, increased Iraqi intelligence capabilities, and the establishment of new military units.[20]

Although the goals of Operation Ramazan were not achieved, some of the results included the liberation of 250 square kilometers and 80 kilometers of Iranian and Iraqi territories respectively, the elimination of the 96th, 12th, and 42nd Armored Brigades, the 88th Mechanized Brigade, and the 55th Mixed Brigade, the destruction of 650 tanks, armored personnel carriers, and 150 vehicles, and shotting down 14 aircraft and 2 helicopters. Furthermore, 100 tanks and armored personnel carriers, along with a large number of weapons, ammunition, and equipment, were captured by Iranian forces.[21]

After Operation Ramazan, there was a two-month period of stagnation followed by the operations Moslim ibn Aqil and Muharram which were carried out in October and November 1982.[22]

[1] Lutfollahzadegan, Ali-Reza, Rozshomar Jang Iran va Araq (The Chronology of the Iran-Iraq War), Book 20: Obur az Marz (Crossing the Border), Tehran: Markaz-e Motaleat va Tahqiqat-e Jang Sepah, 1381, p. 27; Rashid, Mohsen, Atlas-e Jang Iran va Araq (Atlas of the Iran-Iraq War), Tehran: Markaz-e Motaleat va Tahqiqat-e Jang Sepah, 1379, p. 68.

[2] Lutfy, Muhammad Hassan, Hussaini, Seyyed Yaqub, Artesh-e Jomhuri-ye Eslami-ye Iran dar Hasht Sal Defa-e Muqaddas (The Islamic Republic of Iran Army in Eight Years of Sacred Defense), Vol. 6, Tehran: Sazman-e Aqidati Siyasi Artesh-e Jomhuri-ye Eslami-ye Iran, 1376, p. 50.

[3] Lutfollahzadegan, Ali-Reza, Rozshomar Jang Iran va Araq (The Chronology of the Iran-Iraq War), Book 20, p. 27; Rashid, Mohsen, Atlas-e Jang Iran va Araq (Atlas of the Iran-Iraq War), p. 68; Ardestani, Hossein, Tajzie va Tahlil-e Jang Iran va Araq (Analysis of the Iran-Iraq War), Vol. 3: Tanbih-e Motajavez (Punishment of the Aggressor), Tehran: Markaz-e Motaleat va Tahqiqat-e Jang, 1379, p. 33.

[4] Babaei, Gol-Ali, Zarbat-e Motaqabeel (Counterstrike), Tehran: Soreh Mehr, 1388, Pp. 55 and 59.

[5] Jafari, Mojtaba, Atlas-e Nabard-haye Mandegar (Atlas of Enduring Battles), Tehran: Soreh Sabz, 35th edition, 1389, Pp. 78 and 79.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Jafari, Mojtaba, Atlas-e Nabard-haye Mandegar (Atlas of Enduring Battles), p. 78.

[8] Lutfy, Muhammad Hassan, Hussaini, Seyyed Yaqub, Artesh-e Jomhuri-ye Eslami-ye Iran dar Hasht Sal Defa-e Muqaadas (The Islamic Republic of Iran Army in Eight Years of Sacred Defense), Vol. 6, p. 42.

[9] Ibid., p. 50.

[10] Lutfollahzadegan, Ali-Reza, Rozshomar Jang Iran va Araq (The Chronology of the Iran-Iraq War), Book 20, p. 28.

[11] Ibid., Pp. 28 and 29.

[12] Ibid., Pp. 416, 425, 30, 334, 356, 403.

[13] Rashid, Mohsen, Atlas-e Jang Iran va Araq (Atlas of the Iran-Iraq War), p. 68; Babaei, Gol-Ali, Zarbat-e Mutaqabeel (Counterstrike), p. 151.

[14] Lutfollahzadegan, Ali-Reza, Rozshomar Jang Iran va Araq (The Chronology of the Iran-Iraq War), Book 20, Pp. 425, 426.

[15] Ibid., Pp. 416, 417.

[16] Jafari, Mojtaba, Atlas-e Nabard-haye Mandegar (Atlas of Enduring Battles), p. 79.

[17] Rashid, Mohsen, Atlas-e Jang Iran va Araq (Atlas of the Iran-Iraq War), p. 68.

[18] Ibid.; Jafari, Mojtaba, Atlas-e Nabard-haye Mandegar (Atlas of Enduring Battles), Pp. 78-79.

[19] Jafari, Mojtaba, Atlas-e Nabard-haye Mandegar (Atlas of Enduring Battles), p. 79; Dehghan, Ahmad, Nagofteh-haye Jang (Untold Stories of the War), Pp. 324 and 328.

[20] Ardestani, Hussain, Tajzie va Tahlil-e Jang Iran va Araq (Analysis of the Iran-Iraq War), Vol. 3, p. 34.

[21] Jafari, Mojtaba, Atlas-e Nabard-haye Mandegar (Atlas of Enduring Battles), p. 79; Rashid, Mohsen, Atlas-e Jang Iran va Araq (Atlas of the Iran-Iraq War), p. 68.

[22] Ardestani, Hussain, Tajzie va Tahlil-e Jang Iran va Araq (Analysis of the Iran-Iraq War), Vol. 3, p. 34.