Sites

Khorramshahr

Sajjad Naderipour

457 Views

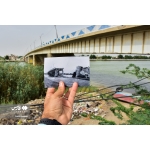

Khorramshahr is a city in Khuzestan Province located between the Karun and Arvand rivers. At the start of the Iran–Iraq War, it fell to Iraqi forces but was liberated on May 24, 1982.

Covering 67.5 square kilometers, Khorramshahr lies at the southwestern tip of Iran, on the Persian Gulf coastline between the Karun and Arvand rivers. It is about 1100 km from Tehran and 125 km from Ahvaz.[1] According to the 2016 census, its population stood at 170976.[2]

Originally known as al-Muhammara, the city traces its roots to the 18th century. During the reign of Shah Abbas I of the Safavid dynasty, Iran decided to construct a port along the Arvand River that would serve as a major trading hub. This plan was implemented under Muhammad Shah Qajar. Al-Muhammara grew into a port city, and a customs station was established nearby to handle trade and shipments. Subsequently, the city became a commercial rival to Basra Port, reducing its revenue and triggering hostilities from the rulers of Baghdad. In 1837, the army of Pasha, the ruler of Baghdad, attacked al-Muhammara, destroying much of the city and killing many men, but it was eventually rebuilt.

The city was officially known as al-Muhammara until 1965 when the government renamed it Khorramshahr.[3]

Before the Iran–Iraq War, Khorramshahr was one of Iran’s wealthiest cities thanks to its strategic location and access to international waters. It hosted major domestic and foreign trading companies and large shipping firms, which had turned the city into an international port. Its residents were typically multilingual, speaking Persian, Arabic, and even European languages. Most locals worked in agriculture (date palms and citrus), and traditional crafts like weaving abayas and robes and mat-making.[4]

One of the key events related to the Iran–Iraq War that occurred between February 1979 and October 1980 was the riots organized by the Arab People’s Movement and led by Sheikh Shubair Khaqani, a prominent cleric in Khorramshahr. Backed by financial and military support from Iraq, Kuwait, and Libya,[5] this movement emerged between February 1979 and mid-1979, demanding autonomy for Khuzestan.[6] During the conflicts, Sheikh Shubair’s followers attacked government and military centers, killing security personnel and civilians.[7] Iranian leaders and authorities, including Ayatollah Khamenei, Mr. Bazargan, Ayatollah Taleqani, Seyyed Ahmad Khomeini, and Imam Khomeini (ra) himself, tried to negotiate a peaceful resolution, but talks failed.[8] On May 30, 1979, armed members of the Arab People’s Movement barricaded streets and attacked police stations and government offices. In response, the forces of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and Army commandos entered Khorramshahr and engaged the insurgents. At the governor’s request, fighter jets from Dezful Air Base also carried out show-of-force flights over the city.[9]

Despite efforts for a peaceful solution, sporadic clashes continued until late July 1979. Finally, the tensions came to an end after Sheikh Shubair was moved to Qom.[10]

One striking aspect of the Arab People’s Movement in Khorramshahr was Iraq’s involvement. Reports from the time highlight the interference of the Iraqi consulate in the city and Iraqi military movements along the border.[11]

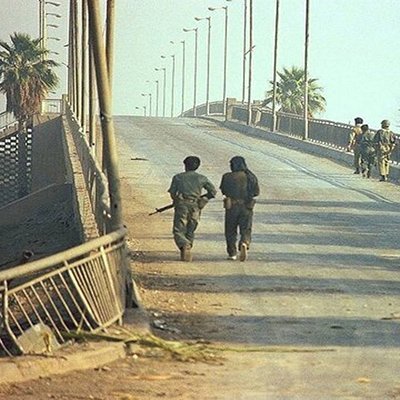

When the Iran–Iraq War broke out, Saddam Hussain’s primary strategic objective in Khuzestan was to seize Khorramshahr.[12] Despite fierce resistance by local defenders, the city fell to Iraqi forces on October 26, 1980, after 33 days of intense fighting.[13] With the collapse of the last defensive positions, the city was completely evacuated and the residents[14] were relocated to nearby towns and other provinces.

After 578 days of occupation, Khorramshahr was liberated on May 24, 1982, during Operation Beit al-Muqaddas. Except for Shalamcheh, Koushk, and Talaieh, which remained under Iraqi control, all other areas were recaptured.[15]

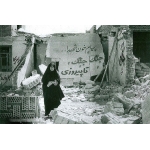

At the suggestion of Ayatollah Ali Eslami, a sign was installed at the entrance of Khorramshahr, reading “Welcome to Khorramshahr – Population: 36 million”. It was handwritten by Martyr Behrouz Moradi and became a powerful symbol of the city’s liberation.[16] The liberation of Khorramshahr shifted the military and political balance of the war and the Persian Gulf region in Iran’s favor. In terms of the military aspects, the success of four consecutive operations in eight months showed Iran’s renewed power and capabilities. Politically, Iraq lost its negotiating leverage and was placed in a weakened position.[17]

Following the liberation of Khorramshahr, the UN Security Council, after a 22-month gap since its last resolution, issued Resolution 514 on July 12, 1982. While the resolution took a relatively firm stance, it still avoided referring to the aggressor or calling for punishment. Meanwhile, the liberation of Khorramshahr raised concerns among Arab states in Western Asia. In addition, major powers such as the U.S. expressed concern over Iran gaining momentum and thus increased their support for Iraq.[18]

Just three days after Iran accepted UN Resolution 598, Iraq attacked southern Iran on July 22, 1988, advancing to 30 km north of Khorramshahr. The Iraqi army aimed to inflict a decisive blow, occupy strategic territories, and take prisoners of war to enhance its leverage during post-war negotiations, particularly regarding the prisoner exchanges. In fact, the reoccupation of Khorramshahr would have been a major bargaining chip for Iraq. In response, Imam Khomeini (ra) called upon the military and the people to defend the country. Finally, after fierce battles, Iraqi forces were forced to retreat.[19]

At the heart of Khorramshahr stands the Grand Mosque. Built in 1871 and reconstructed in 1964, it is the symbol of resisting the enemy throughout the Iran-Iraq War. Initially, the Grand Mosque of Khorramshahr served as a hub for anti-Pahlavi activities. After the Islamic Revolution, it turned into a center for organizing local resistance against the anti-revolutionary elements. For instance, on July 15, 1979, seven civilians were martyred in the mosque courtyard following a grenade attack by anti-revolutionary forces. With the outbreak of the imposed war, the mosque, due to its strategic location and its pivotal role in pre-Revolution activities, became the center of a 35-day popular resistance in Khorramshahr. Accordingly, it served as a command and communication center, a base for logistics, training, and medical aid and a temporary morgue and rally point for volunteers. Martyr Muhammad Jahanara, commander of the Khorramshahr IRGC, along with several Army officers, particularly from the Navy, based their activities in the mosque, which also housed the central communications unit. Accordingly, the site effectively served as the tactical headquarters for defending the city.

On October 20, 1980, the Iraqi forces shelled the mosque for the first time, damaging its dome and killing several people. On the morning of October 25, 1980, fighting intensified within 30 meters of the mosque. By nightfall, the mosque had fallen into enemy hands, and all defenders were ordered to retreat and evacuate the city. Remarkably, the Grand Mosque survived the occupation. When Khorramshahr was liberated, Iranian fighters rushed to the mosque,[20] hung banners, and celebrated victory. On the day Khorramshahr was liberated, it was agreed that all combatants would gather in the Grand Mosque to perform the Noon and Afternoon Prayers in congregation. As they gathered inside, enemy forces shelled the mosque, resulting in the martyrdom of several people and the destruction of its dome.[21] Throughout the eight years of the Iran–Iraq War, 847 of the people of Khorramshahr and its surrounding villages were injured, 88 were taken prisoner of war, and 565 were martyred.[22] Among the martyrs, 247 lost their lives during the 35-day defense of Khorramshahr and 140 during the Iraqi missile and air raids on cities.[23]

The Martyrs’ Cemetery of Khorramshahr not only honors local heroes but also hosts 162 martyrs from 51 cities across Iran, the majority from Tehran, Abadan, Shiraz, and Ahvaz, who came to defend Khorramshahr.[24]

The city’s most notable martyrs include Abdolmahdi Albughubaish, Muhammad-Reza Dashtizadeh, Seyyed Hamid Arjaei, Muhammad-Reza Rabie-Zadeh, Seyyed Muhammad-Ali Jahanara, Behnam Muhammadi-Rad, Behrouz Moradi Qahdarijani, and Abdolreza Mousavi.[25]

Seyyed Muhammad-Ali Jahanara, commander of the Khorramshahr IRGC, played a decisive role in the days of Khorramshahr’s heroic resistance. By organizing local forces and volunteer groups, he mobilized 45 days of resistance against the Baathist army.[26]

In 1996, the Khorramshahr Sacred Defense Museum was inaugurated to commemorate the bravery of Iranians during the war.[27] Today, several memorial sites in and around the city serve as key pilgrimage points for visitors, especially during the Rahian-e Noor tours to southern battlefields. The include Martyrs’ Cemetery of Khorramshahr, Khorramshahr Grand Mosque, Nahr-e Khayn Martyrs Memorial, Imam Hussain (as) Field Hospital, Operation Ramazan Martyrs Memorial, Operation Beit al-Muqaddas Martyrs Memorial, Karbala 5 Memorial Martyrs Memorial (Shalamcheh), and Karbala 4 Martyrs Memorial (Alqameh).[28]

Numerous films have been produced focusing on Khorramshahr during the Iran–Iraq War including Balami Be Souye Sahel (Rasul Mollaqolipour-1985), Kimia (Ahmad-Reza Darvish-1994), Harim-e Mehrvarzi (Nasser Gholamrezaei-1986), Sarzameen-e Khorshid (Ahmad-Reza Darvish-1997), Doel (Ahmad-Reza Darvish-2003), Rooz-e Sevom (Muhammad-Hussain Latifi-2006), Koodak va Fereshteh (Masoud Naqqashzadeh-2008), Bozorgmard-e Koochak (Sadeq Sadeq-Daqiqi- 2011), and 23 Nafar (Mahdi Jafari-2018.[29]

Likewise, books about Khorramshahr form an important part of Iran’s war literature, including Daa (Seyyedeh Azam Hussaini-2008), Safar Be Geray-e 270 Darajeh (Ahmad Dehqan), Poutine-haye Maryam (Maryam Amjadi), Kalk-haye Khaki (Golali Babaei & Hussain Behzad), Pa Be Pay-e Baran (Hedayatollah Behboodi & Morteza Sarhangi), Maamouryat dar Khorramshahr (Colonel Falah al-Lami (Iraqi army officer)), Takavaran-e Nirooye Daryayi Dar Khorramshahr (Seyyed Qassem Yahussaini), and Yekshanbeh Akhar (Masoumeh Ramhormozi).[30]

[1] Sait-e Shahrdari-ye Khorramshahr (Khorramshahr Municipality Website), http://khorramshahr.ir/index.aspx?fkeyid=&siteid=1&pageid=175

[2] Sait-e Markaz-e Amar-e Iran (Statistical Center of Iran Website), https://www.amar.org.ir

[3] Markaz-e Pajohesh-haye Majles-e Showra-ye Eslami, Fath-e Khorramshahr, Noqte-ye Atf-e Defa Muqaddas (Liberation of Khorramshahr, Turning Point of the Sacred Defense), 1378, p. 2.

[4] Ibid., Pp. 2 and 3.

[5] Azari Shahrzaei, Reza, Moruri bar Zohur va Soqout-e Padide-ye Khalq-e Arab 1357-58 (A Review of the Rise and Fall of the Arab People Movement 1978-1979), Faslname Goftogu, No. 25, 1378, Pp. 67-68.

[6] Ibid., Pp. 76 and 68.

[7] Ibid., Pp. 72-76.

[8] Ibid., Pp. 66-67.

[9] Ibid., p. 73.

[10] Ibid., p. 76.

[11] Ibid., Pp. 69 and 74.

[12] Mansouri, Esmaeil, Tajavoz-e Araq, Eshghal-e Khorramshahr va Vakonesh Keshvarha-ye Mantaqe (Iraq’s Aggression, Occupation of Khorramshahr and Reactions of Countries in the Region), Mahname-ye Shahed Yaran, No. 19, Khordad 86, p. 10.

[13] Aminabadi, Seyyed Rouhollah, Bi-parde ba Tarikh / Aban va Azar 1359 - Sokout-e Khorramshahr pas az 33 Rooz-e Moqavemat / Shekast-e Hasr-e Abadan dar Pey-e Farman-e Hazrat-e Emam Khomeini (ra) / Esarat-e Vazir-e Naft / Sharayet-e Iran baraye Azadi-ye Gerogan-ha-ye Amrikayi (Open Talk with History / November-December 1980 - Fall of Khorramshahr after 33 Days of Resistance / Breaking of Abadan Siege by Imam Khomeini’s Order / Captivity of Oil Minister / Iran’s Conditions for Releasing American Hostages), Nashriye-ye Pasdar-e Eslam, No. 393 and 394, Azar 1393, p. 27.

[14] Amarname-ye Ostan-e Khuzestan (1360) (Khuzestan Province Statistical Yearbook), Ahvaz, Sazman-e Barname va Boodje-ye Ostan-e Khuzestan, 1390, p. 13.

[15] Pourhussain, Nasser, Khorramshahr (Azadsazi-ye Khorramshahr) (Khorramshahr (Liberation of Khorramshahr)), Daneshname-ye Jahan-e Eslam, Vol. 15, Tehran, Bonyad-e Daeret al-Maarref-e Eslami, p. 427.

[16] Majera-ye Tablou-ye Mashhour-e Khorramshahr Jamiyat 36 Million Nafar Che Bood? (What was the Story of the Famous Khorramshahr Sign 36 Million Population?), Sait-e Markaz-e Asnad-e Enqelab-e Eslami, https://irdc.ir/fa/news/

[17] Pourhussain, Nasser, Ibid., p. 427.

[18] Ibid., p. 428.

[19] Motlaq, Mohsen, Khorramshahr (Khorramshahr), Tehran, Sazman-e Honari va Adabiat-e Defa Muqaddas, 1393, Pp. 100-103.

[20] Pourjabari, Pejman, Atlas-e Joghrafia-ye Hamasi (Epic Geography Atlas, Khuzestan in War), Khuzestan dar Jang, Tehran, Sarir, 1389, p. 33.

[21] Masjed-e Jame-ye Khorramshahr Namad-e Pirouzi-ye Mellat-e Iran (Khorramshahr Grand Mosque, Symbol of Iran’s Victory), Khabargozari Rasa, code 129229, 3 Khordad 139, https://rasanews.ir/000XcL

[22] Sait-e Shuhaday-e Defa Muqaddas (Sacred Defense Martyrs Website), https://khoramshahr.ostan-khz.ir/

[23] Pourjabari, Pejman, Atlas-e Joghrafia-ye Hamasi (Epic Geography Atlas), Vol. 1, 2nd Edition, Tehran, Entesharat-e Sarir, Pp. 15 and 34.

[24] Ibid., p. 34.

[25] Shuhday-e Defa Muqaddas, https://khoramshahr.ostan-khz.ir/

[26] Savarian, Hassan-Ali, Jahanara Sardamdar-e Nikiha Bood (Jahanara Was the Leader of Kindnesses), Shahed Yaran, No. 72-73, 1390, Pp. 58-61.

[27] Moozei-e Defa Muqaddas-e Khorramshahr, Yadegari az 8 Sal Jang dar Khorramshahr (Khorramshahr Sacred Defense Museum, A Memory of 8 Years of War in Khorramshahr), http://www.yjc.ir/00W1nB

[28] Pourjabari, Pejman, Ibid., Pp. 27, 33, 34, 42, 52, 55, 58, 62.

[29] Revayat-e Hamase-ye Azadsazi-ye Khorramshahr dar Sinama-ye Defa Muqaddas – Kodam Film-ha Sevome Khordad ra be Namayesh Gozaashtand? (Narration of the Khorramshahr Liberation Epic in Sacred Defense Cinema – Which Films Showed the Third of Khordad?), Sait-e Honar Online, code 172958, 2 Khordad 1401, https://www.honaronline.ir

[30] Moarefi 14 Ketab Darbare-ye Khorramshahr (Introduction of 14 Books about Khorramshahr), Khabargozari Rasa, code 565940, 3 Khordad 1397, https://rasanews.ir/002NE4