Sites

Britain

Sajjad Naderipour

169 Views

Located in northwestern Europe, Britain was one of Saddam Hussain’s main backers during the Iran–Iraq War. Covering an area of about 244820 square kilometers, Britain is a large island along the North Atlantic Ocean, the North Sea, and the Irish Sea. It consists of dozens of smaller islands and shares a land border only with the Republic of Ireland to the west. The country is a constitutional monarchy, and its capital is London. Other major cities include Southampton, Birmingham, Manchester, Belfast, Liverpool, Newcastle, Glasgow, Portsmouth, Cardiff, Bristol, Kingston, Edinburgh, and Aberdeen.[1]

The history of diplomatic ties between Iran and Britain goes back to the Safavid era and has gone through many ups and downs. It began when Shah Abbas I received British military assistance to expel the Portuguese from Bandar Abbas[2] and sent Iran’s first ambassador to London.[3] Under Karim Khan Zand, trade relations grew, and British merchants were even exempted from taxes.[4]

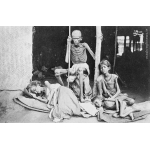

During the Qajar period, relations with Britain deepened, and Iran granted numerous concessions to the British, the most important of which were the Treaty of Gulistan,[5] the Treaty of Turkmenchay,[6] the Reuter Concession,[7] and the D’Arcy Concession.[8] At the same time, Britain played a key role in the dismissal and eventual assassination of Amir Kabir,[9] sought to undermine the Constitutional Revolution,[10] suppressed the uprisings of the people in Tangestan,[11] orchestrated the separation of Herat from Iran,[12] and was a leading factor in the occurrence of the great famine in the country.[13]

Later, Britain backed the rise of the Pahlavi dynasty in Iran to expand its influence in the country. During the reign of Muhammad Reza Shah, Britain played a decisive role in Bahrain’s separation from Iran.[14]

When Mossadeq came to power and nationalized the Iranian oil industry, Britain severed diplomatic ties with Iran and imposed harsh economic sanctions against the country.[15] It was not until the 1953 coup[16]—jointly orchestrated by the U.S. and the UK—that relations were restored under Fazlollah Zahedi’s government.

With the victory of the Islamic Revolution, relations between the two countries again turned cold. When the Iran–Iraq War broke out, Britain, already aware of and even consulted about Saddam’s plan to invade Iran,[17] joined Iraq’s supporters and did everything possible to undermine Iran. Although London initially declared neutrality, its first major move was withdrawing from its agreement to supply Iran with 1500 Chieftain tanks. Moreover, it delivered some of these tanks to Iraq.[18]

Britain also shut down several Iranian government offices and state-owned companies in London under the pretext of preventing arms purchases.[19] As for the intelligence activities, British agencies passed on surveillance data and intercepted communications from Iran’s procurement office in London to Iraq.[20]

Throughout the war, Britain provided Iraq with logistical support and even helped establish domestic arms production inside the country. One major project was the construction of an extensive network of underground shelters, an effort that began in June 1982 with British engineering expertise. These shelters, designed for 48000 soldiers, were equipped for long-term survival. Each steel-reinforced tunnel could hold up to 1200 troops and included command posts, medical stations, decontamination rooms, kitchens, food storage, water supplies, and armories.[21] Furthermore, together with a few other countries, it helped Iraq build a chemical weapons facility near the Samarra–Baghdad highway, capable of producing 60 tons of mustard gas and tabun per month. The raw materials for this plant came from Britain, Germany, the Netherlands, and the European Common Market. These weapons were later used against Iranian forces.[22] Britain also trained Iraqi military personnel. On average, 40 Iraqi fighter pilots received training at Royal Air Force bases each year during the war, with private firms like C.S.I. Aviation supervising the programs.[23]

Despite official statements claiming otherwise, British companies continued selling arms to Iraq throughout the war, exporting over $1.5 billion worth of goods and advanced technology.[24] In March 1982, London approved the sale of advanced tanks to Iraq worth $1 billion and even resumed negotiations to supply 300 Hawk missiles for an additional $2 billion.[25]

The surge in Iraqi military procurement during the war turned out to be a major opportunity for British machine-tool firms as exporting British machine-tools to Iraq increased from $2.9 million in 1986 to $31.5 million in 1987.[26]

Still, despite its deep involvement, Britain avoided confrontation with Iran during the Tanker War, refraining from deploying 80 percent of its naval fleet and assets to the Persian Gulf.[27]

Britain’s support for Iraq was not limited to military aid, and it extended into diplomacy as well. For example, when the U.S. Navy shot down Iran Air Flight, killing hundreds of civilians, Britain was quick to side with the United States.[28]

A few months after the war ended, Britain reopened its embassy in Tehran, restoring full diplomatic relations. In the years that followed, London played an active role in negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program.

After the assassination of Sadeq Sharafkandi (Secretary-General of the Democratic Party of Kurdistan) in Berlin’s Mykonos restaurant, Britain joined other European nations in recalling its ambassador from Tehran. However, as this policy proved ineffective, its ambassador came back to Iran.[29]

Tensions flared again in November 2011, when Iranian university students stormed the British embassy in Tehran. In response, London expelled Iranian diplomats and shut down its embassy in Tehran, prompting Iran to do the same in London.[30] It took four years before ties were fully restored.[31]

[1] Majalle-Name Otaq-e Bazargani, No. 12, Esfand 1386, Pp. 20-21.

[2] Mahmoud, Mahmoud, Tarikh Ravabet-e Siyasi Iran va Englis dar Qarn-e Nozdahom Miladi, Vol. 1 (History of Political Relations between Iran and Britain in the 19th Century), Tehran, Eqbal, 4th Edition, 1353, p. 4.

[3] Dennis, Wright, Iranian dar Mian-e Englisiha, tarjome Karim Emami (Iranians among the British People), Tehran, Nashr-e No, 2nd Edition, 1368, p. 18.

[4] Mahmoud, Mahmoud, Ibid, Pp. 5-7.

[5] Ibid., Pp. 151-173.

[6] Ibid., Pp. 260-274.

[7] Rozname Hamdeli (Hamdeli Newspaper), sal-e haftom, No. 1983, doshanbeh 3 Mordad 1401, p. 8.

[8] Raeisi, Mina, Emtiaz-e Dorsy (The D’Arcy Concession), Faslname Motaleat-e Tarikhi, No. 37, Tabestan 1391, Pp. 186-188.

[9] Mahmoud, Mahmoud, Ibid, p. 260.

[10] Englis ba Tabdil-e Nehzat-e Edalatkhane be Mashroute Enteqam Gereft (Britain Took Revenge by Turning the Justice Movement into Constitutionalism), https://psri.ir/?id=nuh4gsb0

[11] Reshadat-e Daliran-e Tangestan dar Barabar-e Tajavoz-e Qovah-ye Englis (Bravery of Tangestan’s Braves against British Forces), https://irdc.ir/0001r3

[12] Hunt, Captain, Jang-e Englis va Iran dar Sal 1273 H.Q (The Anglo-Persian War in 1856), Tehran, Sherkat-e Sahami Chap, 1327, Pp. 22-23.

[13] Majd, Muhammadqoli, Qahti-ye Bozorg (The Great Famine), Tehran, Moassesei-e Motaleat va Pajoheshha-ye Siyasi, 1386, Pp. 121-165.

[14] Joda Shodan-e Bahrain az Iran (Separation of Bahrain from Iran), https://psri.ir/?id=nema91nb

[15] Houshang, Mahdavi Abdolreza, Siasat-e Khareji-ye Iran dar Dowran-e Pahlavi 1300-1357 (Iran’s Foreign Policy in the Pahlavi Era 1921-1979), Tehran, Entesharat-e Alborz, 1373, Pp. 192, 193.

[16] Maki, Hussain, Koodetay-e 28 Mordad 1332 va Roidadha-ye Motaaqeb An (The 1953 Coup and Subsequent Events), Tehran, Entesharat-e Elmi, 1378, p. 128.

[17] Englis az Hamle-ye Araq be Iran Etelaa Dasht (Britain Knew about Iraq’s Attack on Iran), http://tarikhirani.ir/fa/news/5613

[18] https://inews.co.uk/news/world/britain-owes-iran-450m-might-finally-pay-back-104060

[19] Qaderi Kangavari, Rouhollah, Tahlili bar Mizan-e Komak-haye Maliy-e Taslihati Mantaqei va Faramantaqei be Araq dar Jang-e Tahmili alayh-e Iran (An Analysis of the Amount of Regional and Extra-regional Military Aid to Iraq in the Iran-Iraq War), Faslname Negin Iran, No. 32, Bahar 1389, p. 61.

[20] Dorudian, Muhammad, Seiri dar Jang-e Iran va Araq, Vol. 6 (A Journey through the Iran-Iraq War), Tehran, Markaz-e Motaleat va Tahqiqat-e Jang, 1376, p. 135.

[21] Ibid., p. 76.

[22] Ibid., Pp. 115-116.

[23] Keshvar Tajhizkonande Saddam dar Jang ba Iran (Saddam’s Supplier Country in the War with Iran), https://irdc.ir/fa/news/99/80-

[24] Dorudian, Muhammad, Aghaz ta Payan, Vol. 7 (From Beginning to End), Tehran, Markaz-e Motaleat va Tahqiqat-e Jang, 1397, p. 135.

[25] Salehi, Hamid, Naqhsh-e Qodrat-ha-ye Bozorg dar Jang-e Araq alayh-e Iran (Role of Great Powers in the Iraq-Iran War), Tehran, Mizan, 1391, p. 136.

[26] Khabargozari Defa Muqaddas (Sacred Defense News Agency), Khedmat-e Englis be Saddam dar Jang-e Tahmili (Britain’s Services to Saddam in the Iran-Iraq War), code 380190, 29 Dey 1398.

[27] Kardzman, Anthony, Gharb va Monazeie Daryaei dar Khalij-e Fars – 1987 (West and Maritime Conflict in the Persian Gulf – 1987), tarjome Parisa Kariminia, Faslname Negin Iran, Tabestan 1382, No. 5, p. 68.

[28] Efshaye Komak-e Englis be Lapoushani Jenayat-e Amrika dar Khalij-e Fars (Disclosure of Britain’s Help to Cover up U.S. Crimes in the Persian Gulf), sit-e IRNA.

[29] Bazkhan-i Shekast-e Tootei-e Gharb alayh-e Iran dar Majera-ye Mikonos (Review of the West’s Failed Conspiracy against Iran in the Mykonos Issue), https://irdc.ir/000122

[30] Dar Vakonesh be Tatili-ye Sefarat-e Iran dar Landan – Tamami Diplomat-ha va Karkonan-e Sefarat-e Englis az Iran khrej Mishavand (In Response to the Closure of the Iranian Embassy in London – All Diplomats and Staff of the British Embassy Will Be Expelled from Iran), hamshahrionline.ir/x3jCc

[31] Tasavir-e Bazgoshayi-ye Sefarat-e Englis dar Tehran (Images of Reopening of the British Embassy in Tehran), https://fararu.com/fa/news/244359

![A shocking photo of the depth of the British crimes in Iran | The photo dates back to 1297 or 1298 AH, and the photographer is unknown. The original is kept in the War Memorial Museum in Australia.

The caption reads: “This photo was taken in the desert near the city of Bijar. [In the final years of World War I] British forces have entered Iran from Turkey and Syria and are moving towards Tehran. They have beheaded a sheep to cook for the British soldiers. The butcher has thrown away the sheep’s intestines and entrails, and hungry people have rushed to pick up the filth, and someone has recorded this photo.”](../attach/attachthumbnail.php?id=1754881983.png)