Battles

Operation Valfajr 10

Akram Jafarabadi

155 Views

Operation Valfajr 10 began on March 14, 1988, in Nosoud, Iran, and Halabja, Iraq, under the code-name “Ya Rasulullah (pbuh)”. The operation concluded after six days.

Due to the decreasing effectiveness of operational strategies adopted on the southern frontlines which made gaining success unlikely, the commanders of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) shifted their focus to the northwest, specifically Maowat region of Iraq.[1]

Moreover, challenges and shortcomings in continuing Operation Beit al-Muqaddas 2—particularly the enemy’s vigilance, destruction of roads and the Garde-Rash Bridge due to river flooding, blocked supply lines, heavy snowfall, and enemy attacks on Kurdish opposition groups supporting the Islamic Republic in liberated areas—gradually directed attention towards the general area of Halabja and the Darbandikhan Dam.[2]

The Iranian forces aimed to capture Halabja, Khurmal, Doujaila, Byara, and Tawella,[3] with the Halabja region and the Darbandikhan Dam considered the primary operational zone.[4]

According to the plan of the operation, three headquarters would engage in the battle: Qods in the northern part of the operational area, Thamen al-Aemmah (as) in the center, and Fath Headquarters in the south.[5] Also, 10 divisions and 13 brigades, each operating at approximately 50 percent of their full capacity, were organized into 70 battalions.[6]

The operation commenced at 8:23 PM on the eve of Eid al-Mabaath, under the code-name “Ya Rasulullah (pbuh)”, covering an 85-kilometer area. The Iranian troops were engaged in three fronts including Marivan, Paveh, and Darbandikhan Dam. In the first phase, they liberated Khurmal and its surrounding villages. During the second phase, after a fierce battle and destroying enemy forces, Iranian troops liberated the strategic town of Doujaila[7] and twenty nearby villages. Doujaila is a small town located east of the Darbandikhan Lake, about ten kilometers north of Halabja, with several military and economic installations including the important Zamaqi Garrison.[8]

In the third phase, Iranian fighters captured the Balambo, Shindrooy, and Teymorzhanan heights, gaining access to the Halabja and capturing many senior commanders of the Iraqi army.

The fourth phase resulted in the liberation of the Kurdish town of Nosoud in Iran, which had been under Iraqi control for over seven years. Consequently, the military towns of Byara and Tawella were also freed. Fearing defeat in the operational area, Saddam’s regime targeted Halabja with chemical weapons, causing a massacre comparable to the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Japan.

In the fifth phase, 19 heights between the Khurmal–Seyyed Sadeq area in the Sulaymaniyah Province were liberated, including the 1058-meter-high Rishan Peak, which overlooked Seyyed Sadeq city and a number of nearby villages.[9]

It was anticipated that by capturing Darbandikhan Dam and blocking the Sulaymaniyah road, Iraqi army reserves from the south would be forced to move northward, suffering heavy casualties similar to those experienced in Shalamcheh and Faw. However, the Iraqi high command refused to deploy southern reserve units to recapture Halabja and instead decided to use weapons of mass destruction.[10]

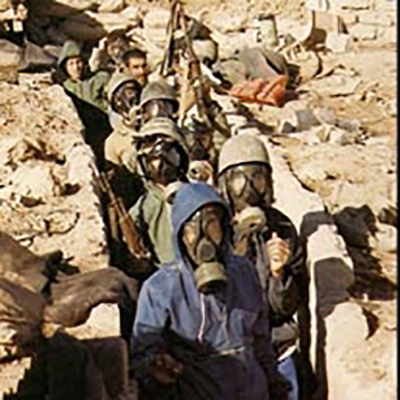

On midday March 16, 1988, as groups of Halabja residents were moving towards the Iranian borders, Iraqi aircraft stoke the area with chemical bombs[11] and within moments, a large number of defenseless civilians were martyred because of inhaling toxic gases.[12]

Immediately afterwards, the units of Fath and Thamen al-Aemmah (as) headquarters sought to help the affected civilians, evacuating them to the Iranian borders, and treating the injured. In the meantime, some units from the Qods Headquarters reinforced the northern flank of the operation.[13]

The global communities, political circles, and media organizations turned a blind eye to this widespread massacre in the days following the attack.[14] However, the Islamic Republic of Iran tried to publicize the scale of the tragedy and appealed for international aid to provide medical treatment for the victims.[15] About a week after the chemical attack, with the presence of media representatives, the first relatively extensive reports of the massacre were published.[16] Furthermore, sending some chemical victims from Halabja to several European countries and the United States for treatment, and broadcasting their images—mostly women and children—caused the global condemnation of Iraq. For the first time, the United Nations Secretary-General condemned Iraq for its use of chemical weapons. Meanwhile, the US government claimed there was evidence of Iran’s use of chemical shells against Iraqi forces. Taking advantage of this situation, Iraq also made the same claim requesting the dispatch of representatives of the UN Secretary-General to Baghdad.[17]

As a result of this operation, over 1000 square kilometers of the territory east of Darbandikhan Lake—including the cities of Halabja, Khurmal, Doujaila, Byara, and Tawella, dozens of villages, and the Iranian border city of Nosoud—were liberated.[18] Approximately 5400 enemy soldiers were captured, and more than 10000 were killed or wounded.

Totally, 270 tanks and armored personnel carriers were destroyed, and over 90 were captured. Moreover, 115 artillery pieces were seized, and 73 artillery guns, along with 10 aircraft and one helicopter, were destroyed.[19]

In a message on the occasion of this victory, Imam Khomeini (ra) said:

“The news of the victories and epic deeds of the valiant army of Islam not only delighted the heart of our nation, being the heart of all the downtrodden and deprived, it also agonized the heart of Saddam as well his supporters and masters, especially America and Israel”.[20]

Following Operation Valfajr 10, the imposed war entered a new phase.[21] Iran’s opposition to UN Resolution 598 became a pretext for Iraq to continue its attacks. Meanwhile, aiming to concentrate forces against possible Iraqi offensives and as the international developments required, Iran withdrew from some occupied areas.[22] Realizing that no large-scale operations would take place in the south, Iraq prepared to attack Faw.[23] By recapturing Faw, Iraq reoccupied territories previously seized by Iran within less than three months.[24] After Iran’s withdrawal from the northern front, Halabja was the last area to be evacuated.[25]

A memorial commemorating Operation Valfajr 10 and Operation Muhammad Rasulullah (pbuh) is under construction on the Dalani Heights, overlooking the border towns of Khurmal, Halabja, Seyyed Sadeq, and Darbandikhan Dam in Iraq.[26]

[1] Yazdi, Yadollah, Rouzshomar-e Jang-e Iran va Araq (Chronology of the Iran-Iraq War), Book No. 54, Tehran, Markaz-e Asnad va Tahqiqat-e Defa Muqaddas-e Sepah, 1392, p. 17.

[2] Doroodian, Muhammad, Seiri dar Jang-e Iran va Araq (A Survey of the Iran-Iraq War), Vol. 4, Tehran, Markaz-e Sepah, 1376, p. 217.

[3] Rashid, Mohsen, Atlas-e Jang-e Iran va Araq (Atlas of the Iran-Iraq War), Tehran, Markaz-e Asnad va Tahqiqat-e Defa Muqaddas-e Sepah, 2nd ed., 1389, p. 99.

[4] Doroodian, Muhammad, Ibid., p. 218.

[5] Yazdi, Yadollah, Ibid., p. 17.

[6] Doroodian, Muhammad, Ibid., p. 222.

[7] Mahmoudzadeh, Nosratollah, Marsiye-ye Halabcheh (Elegy for Halabja), Tehran, Raja, 2nd ed., 1368, Pp. 12–13.

[8] Ibid., p. 23.

[9] Ibid., Pp. 12–13.

[10] Rashid, Mohsen, Ibid., p. 99.

[11] Jafari, Mojtaba, Atlas-e Nabardhaye Mandegar (Atlas of Lasting Battles), 35th ed., 1393, Tehran, Sura Sabz, p. 148.

[12] Yazdi, Yadollah, Ibid., p. 20.

[13] Ibid., p. 21.

[14] Rashid, Mohsen, Ibid., p. 99.

[15] Yazdi, Yadollah, Ibid., p. 21.

[16] Ibid., p. 22.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid., p. 20.

[19] Jafari, Mojtaba, Ibid., p. 148.

[20] Mahmoudzadeh, Nosratollah, Ibid., p. 9.

[21] Rashid, Mohsen, Ibid., p. 106.

[22] Doroodian, Muhammad, Seiri dar Jang-e Iran va Araq (A Survey of the Iran-Iraq War), Vol. 5, Tehran, Markaz-e Sepah, 1378, p. 136.

[23] Doroodian, Muhammad, Ibid., Vol. 4, p. 236.

[24] Ibid., p. 248.

[25] Ibid., Vol. 5, p. 136.

[26] Sit-e Rahian-e Noor (Rahian-e Noor Website), https://www.rahianenoor.com/fa/news/14986.